```{r setup, include=FALSE}

require(Hmisc)

require(qreport)

hookaddcap() # make knitr call a function at the end of each chunk

# to try to automatically add to list of figure

options(prType='html')

getRs('qbookfun.r')

knitr::set_alias(w = 'fig.width', h = 'fig.height',

cap = 'fig.cap', scap = 'fig.scap')

```

`r apacue <- 0`

# Serial Data {#sec-serial}

`r mrg(ddisc(19))`

[For more information see [RMS Chapter 7](https://hbiostat.org/doc/rms.pdf)]{.aside}

## Introduction

`r mrg(sound("serial-1"))` `r ipacue()`

Serial data, also called longitudinal data, repeated measures, or

panel data,

present a special challenge in that the response variable is

multivariate, and that the responses measured at different times (or

other conditions such as doses) but on the same subject are correlated

with each other. One expects correlations between two

measurements measured closer together will exceed correlations for two

distant measurements on the same subject. Analyzing the repeated

measurements just as

though they were independent measurements falsely inflates the sample

size and results in a failure to preserve type I error and confidence

interval coverage. For example, having three measurements on 10

subjects results in 30 measurements, but depending on the correlations

among the three measurements within subject, the effective sample size

might be 16, for example. In other words, the statistical information

for collecting 3 measurements on each of 10 subjects might provide the

same statistical information and power as having one measurement on

each of 16 subjects. The statistical information would however be less than

that from 30 subjects measured once, if the intra-subject correlation

exceeds zero.

The most common problems in analyzing serial data are `r ipacue()`

1. treating repeated measurements per subject as if they were from separate subjects

1. using two-way ANOVA as if different measurement times corresponded to different groups of subjects

1. using repeated measures ANOVA which assumes that the correlation between any two points within subject is the same regardless of how far apart the measures were timed

1. analyzing more than 3 time points as if time is a categorical rather than a continuous variable

* multiplicity problem

* analyses at different times may be inconsistent since times are not connected

* loss of power by not jointly analyzing the serial data

## Analysis Options

`r ipacue()`

There are several overall approaches to the analysis of serial

measurements. Some of the older approaches such as multiple $t$-tests

and repeated measures ANOVA are

now considered obsolete because of the availability of better methods that are

more flexible and robust^[Repeated measures ANOVA makes stringent assumptions and requires complex adjustments for within-subject correlation.].

Separate $t$-tests at each time point do not make good use of

available information, use an inefficient estimate of $\sigma^2$, do

not interpolate time points, and have multiple comparison problems.

Since a multiplicity adjustment for multiple correlated $t$-tests is

not model-based, the resulting confidence intervals and $P$-values

are conservative. To preserve type I error, one always must sacrifice

type II error, but in this case the sacrifice is too severe.

In addition, investigators are frequently confused by the $t$-test being

"significant" at one time point and not at another, and make the

unwarranted claim that the treatment is effective only at the first

time. Besides not recognizing the _absence of evidence is not evidence for absence_ problem, the investigator can be mislead by

increased variability in response at the second time point driving

the $t$ ratio towards zero. This variability may not even be real but

may reflect instability in estimating $\sigma$ separately at each time

point.

Especially when there are more than three unique measurement times, it is advisable to model time as a continuous variable. When estimation of the time-response profile is of central importance, that may be all that's needed. When comparing time-response profiles (e.g., comparing two treatments) one needs to carefully consider the characteristics of the profiles that should be tested, i.e., where the type I and II errors should be directed, for example `r ipacue()`

* difference in slope

* difference in area under the curve

* difference in mean response at the last planned measurement time

* difference in mean curves at _any_ time, i.e., whether the curves have different heights or shapes anywhere

The first 3 are 1 d.f. tests, and the last is a 2 d.f. test if linearity is assumed, and $> 2$ d.f. if fitting a polynomial or spline function.

### Joint Multivariate Models

`r ipacue()`

This is the formal fully-specified statistical model approach whereby

a likelihood function is formed and maximized. This handles highly

imbalanced data, e.g., one subject having one measurement and another

having 100. It is also the most robust approach to non-random subject

dropouts. These two advantages come from the fact that full

likelihood models "know" exactly how observations from the same

subject are connected to each other.

Examples of full likelihood-based models include

generalized least squares (GLS), mixed effects models, and Bayesian hierarchical

models. GLS only handles continuous $Y$ and assumes multivariate

normality. It does not allow different subjects to have different

slopes. But it is easy to specify and interpret, to have its assumptions

checked, and it runs faster.

Mixed effects models can handle multiple hierarchical levels (e.g.,

state/hospital/patient) and random slopes whereby subjects can

have different trajectories. Mixed effects models can be generalized

to binary and other endpoints but lose their full likelihood status

somewhat when these extensions are used, unless a Bayesian approach is used.

* Mixed effects model have random effects (random intercepts and possibly also random slopes or random shapes) for subjects

* These allow estimation of the trajectory for an individual subject

* When the interest is instead on group-level effects (e.g., average difference between treatments, over subjects), GLS squares models may be more appropriate

* The generalization of GLS to non-normally distributed $Y$ is _marginalized models_ (marginalized over subject-level effects)

GLS, formerly called growth curve models, is the

oldest approach and has excellent performance when $Y$ is

conditionally normally distributed.

### GEE

`r ipacue()`

_Generalized estimating equations_ is usually based on a working

independence model whereby ordinary univariate regressions are fitted on a

combined dataset as if all observations are uncorrelated, and then an

after-the-fit correction for intra-cluster

correlation is done using the cluster sandwich covariance estimator or the

cluster bootstrap. GEE is very non-robust to non-random subject dropout; it

assumes missing response values are missing completely at random. It

may also require large sample sizes for

$P$-values and confidence intervals to be accurate. An advantage of GEE is

that it extends easily to every type of response variable, including binary,

ordinal, polytomous, and time-to-event responses.

### Summary Measures

`r mrg(sound("serial-2"))` `r ipacue()`

A simple and frequently effective approach is to summarize the serial

measures from each subject using one or two measures, then to analyze

these measures using traditional statistical methods that capitalize

on the summary measures being independent for different subjects.

This has been called `r ipacue()`

1. Two-stage derived variable analysis [@dig02ana]

1. Response feature analysis [@dup08sta]

1. Longitudinal analysis through summary measures [@mat90ana]

An excellent overview may be found in @mat90ana,

@dup08sta (Chapter 11), and @sen00rep.

Frequently chosen summary measures include the area under the

time-response curve, slope, intercept, and consideration of multiple

features simultaneously, e.g., intercept, coefficient of time,

coefficient of time squared when fitting each subject's data with a

quadratic equation. This allows detailed analyses of curve shapes.

## Case Study

### Data and Summary Measures

`r mrg(sound("serial-3"))` `r ipacue()`

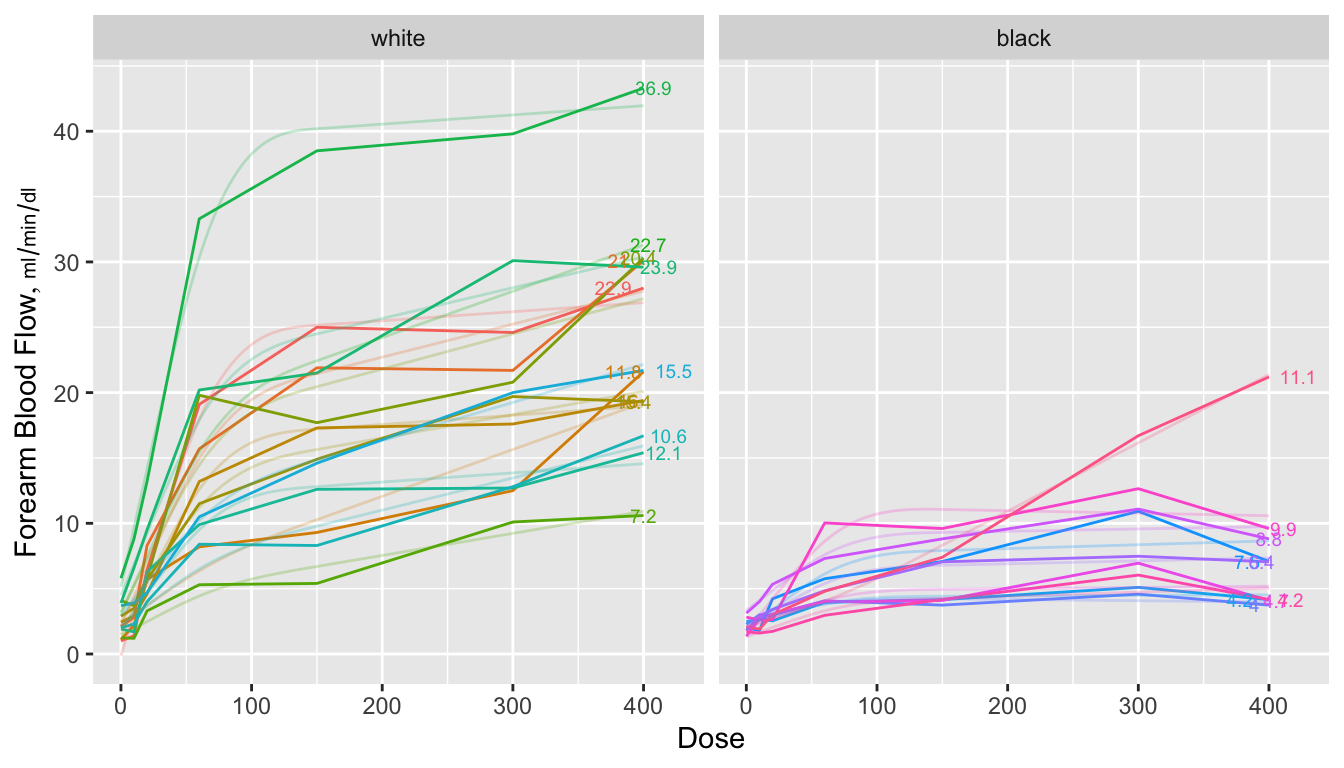

Consider the isoproterenol dose-response analysis [@dup08sta] of

the original data from Lang^[CC Lang etal NEJM 333:155-60, 1995]. Twenty two normotensive men were studied, 9 of

them black and 13 white. Blood flow was measured before the drug was

given, and at escalating doses of isoproterenol. Most subjects had 7

measurements, and these are not independent. **Note**: Categorization of race is arbitrary and represents a gross oversimplification of genetic differences in physiology.

```{r download}

require(Hmisc)

require(data.table) # elegant handling of aggregation

require(ggplot2)

d <- csv.get('https://hbiostat.org/data/repo/11.2.Long.Isoproterenol.csv')

d <- upData(d, keep=c('id', 'dose', 'race', 'fbf'),

race =factor(race, 1:2, c('white', 'black')),

labels=c(fbf='Forearm Blood Flow'),

units=c(fbf='ml/min/dl'))

setDT(d, key=c('id', 'race'))

```

`r ipacue()`

```{r spag,w=7,h=4,cap="Spaghetti plots for isoproterenol data showing raw data stratified by race. Next to each curve is the area under the curve divided by 400 to estimate the mean response function. The area is computed analytically from a restricted cubic spline function fitted separately to each subject's dose-response curve. Shadowing the raw data are faint lines depicting spline fits for each subject",scap='Spaghetti plots for isoproterenol data'}

#| label: fig-serial-spag

# Fit subject-by-subject spline fits and either return the coefficients,

# the estimated area under the curve from [0,400], or evaluate each

# subject's fitted curve over a regular grid of 150 doses

# Area under curve is divided by 400 to get a mean function

require(rms)

options(prType='html')

g <- function(x, y, what=c('curve', 'coef', 'area')) {

what <- match.arg(what) # 'curve' is default

knots <- c(20, 60, 150)

f <- ols(y ~ rcs(x, knots))

xs <- seq(0, 400, length=150)

switch(what,

coef = {k <- coef(f)

list(b0 = k[1], b1=k[2], b2=k[3])},

curve= {x <- seq(0, 400, length=150)

list(dose=xs, fbf=predict(f, data.frame(x=xs)))},

area = {antiDeriv = rcsplineFunction(knots, coef(f),

type='integral')

list(dose = 400, fbf=y[x == 400],

area = antiDeriv(400) / 400,

tarea = areat(x, y) / 400)} )

}

# Function to use trapezoidal rule to compute area under the curve

areat <- function(x, y) {

i <- ! is.na(x + y)

x <- x[i]; y <- y[i]

i <- order(x)

x <- x[i]; y <- y[i]

if(! any(x == 400)) NA else

sum(diff(x) * (y[-1] + y[-length(y)]))/2

}

w <- d[, j=g(dose, fbf), by = list(id, race)] # uses data.table package

a <- d[, j=g(dose, fbf, what='area'), by = list(id, race)]

ggplot(d, aes(x=dose, y=fbf, color=factor(id))) +

geom_line() + geom_line(data=w, alpha=0.25) +

geom_text(aes(label = round(area,1)), data=a, size=2.5,

position=position_dodge(width=50)) +

xlab('Dose') + ylab(label(d$fbf, units=TRUE, plot=TRUE)) +

facet_grid(~ race) +

guides(color=FALSE)

```

`r ipacue()`

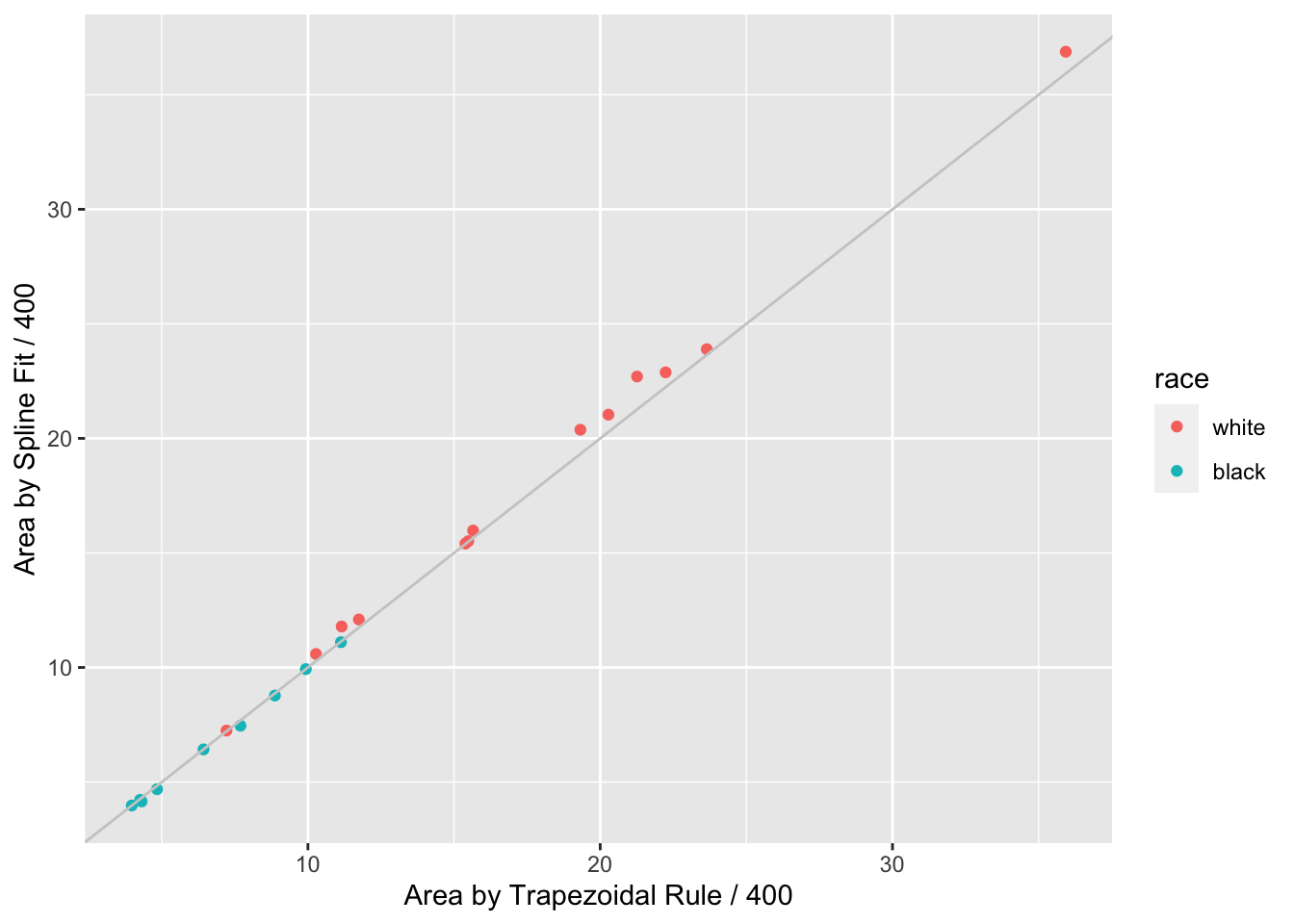

```{r auctwo,cap='AUC by curve fitting and by trapezoidal rule'}

#| label: fig-serial-auctwo

ggplot(a, aes(x=tarea, y=area, color=race)) + geom_point() +

geom_abline(col=gray(.8)) +

xlab('Area by Trapezoidal Rule / 400') +

ylab('Area by Spline Fit / 400')

```

When a subject's dose (or time) span includes the minimum and maximum values

over all subjects, one can use the trapezoidal rule to estimate the area under

the response curve empirically. When interior points are missing, linear

interpolation is used. The spline fits use nonlinear interpolation, which is

slightly better, as is the spline function's assumption of continuity in the

slope. @fig-serial-auctwo compares the area under the curve (divided

by 400 to estimate the mean response) estimated using the the two methods.

Agreement is excellent. In this example, the principle advantage of the spline

approach is that slope and shape parameters are estimated in the process, and

these parameters may be tested separately for association with group (here,

race). For example, one may test whether slopes differ across groups, and

whether the means, curvatures, or inflection points differ. One could

also compare AUC from a sub-interval of $X$.

`r ipacue()`

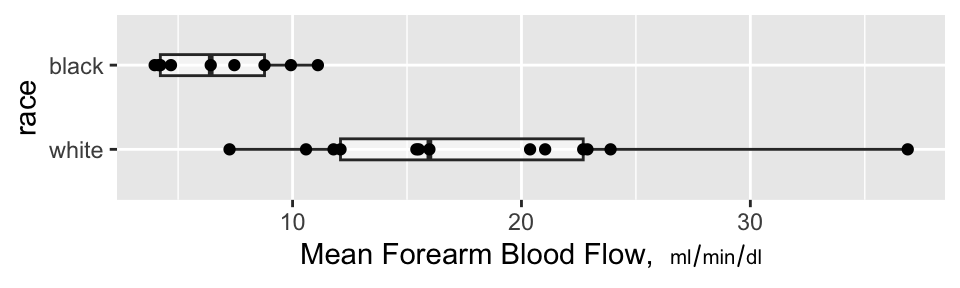

```{r auc,w=5,h=1.5,cap='Mean blood flow computed from the areas under the spline curves, stratified by race, along with box plots',scap='Mean blood flow by race'}

#| label: fig-serial-auc

ggplot(a, aes(x=race, y=area)) +

geom_boxplot(alpha=.5, width=.25) + geom_point() + coord_flip() +

ylab(expression(paste('Mean Forearm Blood Flow, ', scriptstyle(ml/min/dl))))

```

### Nonparametric Test of Race Differences in AUC

`r mrg(sound("serial-4"))`<br>

`r ipacue()`

A minimal-assumption approach to testing for differences in

isoproterenol dose-response between races is to apply the Wilcoxon

test to the normalized AUCs (mean response functions).

```{r wil}

wilcox.test(area ~ race, data=a, conf.int=TRUE)

```

There is strong evidence that the mean response is greater for whites.

### Nonparametric Test of General Curve Differences

`r ipacue()`

@obr88com proposed a method for using logistic regression to

turn the Hotelling $T^2$ test on its side. The Hotelling test is the

multivariate analog of the two-sample $t$-test, and can be used to

test simultaneously such things as whether a treatment modifies either

systolic or diastolic blood pressure. O'Brien's idea was to test

whether systolic or diastolic blood pressure (or both) can predict

which treatment was given. Here we use the idea to test for race

differences in the shape of the dose-response curves. We do this by

predicting race from a 3-predictor model---one containing the intercept, the next the coefficient of the linear dose effect and the third the coefficient of the nonlinear restricted cubic spline term (differences in cubes).

These coefficients were estimated

using ordinary least squares in separately predicting each subject's relationship

between dose and forearm blood flow.

```{r coefs}

h <- d[, j=g(dose, fbf, what='coef'), by = list(id, race)]

h

f <- lrm(race ~ b0 + b1 + b2, data=h, x=TRUE, y=TRUE)

f

```

`r ipacue()`

The likelihood ratio $\chi^{2}_{3}=19.73$ has $P=0.0002$ indicating strong evidence that the races have different averages,

slopes, or shapes of the dose-response curves. The $c$-index of 0.957

indicates nearly perfect ability to separate the races on the basis of three

curve characteristics (although the sample size is small). We can use

the bootstrap to get an overfitting-corrected index.

```{r boot}

set.seed(2)

v <- validate(f, B=1000)

v

```

The overfitting-corrected $c$-index is $c = \frac{D_{xy} + 1}{2}$ = `r round((v['Dxy','index.corrected'] + 1) / 2, 2)`.

### Model-Based Analysis: Generalized Least Squares

`r mrg(sound("serial-5"))` `r ipacue()`

Generalized least squares (GLS) is the first generalization of ordinary

least squares (multiple linear regression). It is described in detail

in _Regression Modeling Strategies_ Chapter 7 where a

comprehensive case study is presented. The assumptions of GLS are `r ipacue()`

* All the usual assumptions about the right-hand-side of the model

related to transformations of $X$ and interactions

* Residuals have a normal distribution

* Residuals have constant variance vs. $\hat{Y}$ or any $X$ (but

the G in GLS also refers to allowing variances to change across $X$)

* The multivariate responses have a multivariate normal

distribution conditional on $X$

* The correlation structure of the conditional multivariate distribution is correctly specified

With fully specified serial data models such as GLS, the fixed effects

of time or dose are modeled just as any other predictor, with the only

difference being that it is the norm to interact the time or dose

effect with treatment or whatever $X$ effect is of interest. This

allows testing hypotheses such as `r ipacue()`

* Does the treatment effect change over time? (time $\times$

treatment interaction)

* Is there a time at which there is a treatment effect? (time

$\times$ treatment interaction + treatment main effect combined into

a chunk test)

* Does the treatment have an effect at time $t$? (difference of

treatments fixing time at $t$, not assuming difference is constant

across different $t$)

In the majority of longitudinal clinical trials, the last hypothesis is the most important, taking $t$ as the end of treatment point. This

is because one is often interested in where patients ended up, not

just whether the treatment provided temporary relief. `r ipacue()`

Now consider the isoproterenol dataset and fit a GLS model allowing for

the same nonlinear spline effect of dose as was used above, and

allowing the shapes of curves to be arbitrarily different by race. We

impose a continuous time AR1 correlation structure on within-subject

responses. This is the most commonly used correlation structure; it

assumes that the correlation between two points is exponentially

declining as the difference between two times or doses

increases.

We fit the GLS model and examine the equal variance assumption.

`r ipacue()`

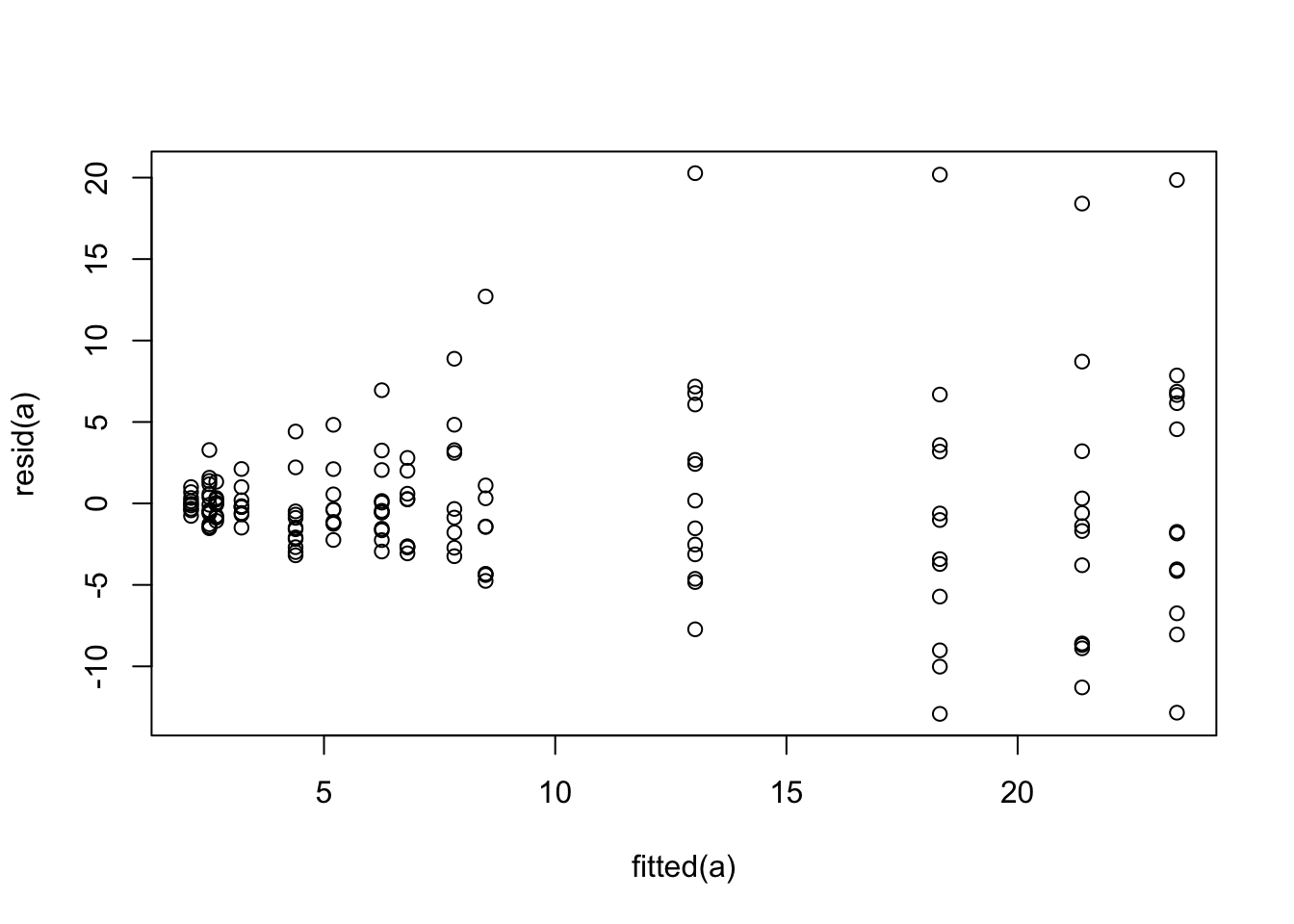

```{r glsa,cap='Residual plot for generalized least squares fit on untransformed `fbf`'}

#| label: fig-serial-glsa

require(nlme)

dd <- datadist(d); options(datadist='dd')

a <- Gls(fbf ~ race * rcs(dose, c(20,60,150)), data=d,

correlation=corCAR1(form = ~ dose | id))

plot(fitted(a), resid(a))

```

The variance of the residuals is clearly increasing with increasing

dose. Try log transforming both `fbf` and dose. The log

transformation requires a very arbitrary adjustment to dose to handle zeros.

```{r glsb}

a <- Gls(log(fbf) ~ race * rcs(log(dose + 1), log(c(20,60,150)+1)), data=d,

correlation=corCAR1(form = ~ dose | id))

anova(a)

```

There is little evidence for a nonlinear dose effect on the log scale,

`r mrg(sound("serial-6"))`

implying that the underlying model is exponential on the original $X$

and $Y$ scales. This is consistent with @dup08sta. Re-fit the

model as linear in the logs. Before taking this as the final model,

also fit the same model but using a correlation pattern based on time

rather than dose. Assume equal time spacing during dose escalation. `r ipacue()`

```{r glstwocorr}

a <- Gls(log(fbf) ~ race * log(dose + 1), data=d,

correlation=corCAR1(form = ~ dose | id))

d$time <- match(d$dose, c(0, 10, 20, 60, 150, 300, 400)) - 1

b <- Gls(log(fbf) ~ race * log(dose + 1), data=d,

correlation=corCAR1(form = ~ time | id))

AIC(a);AIC(b)

b

anova(b)

```

Lower AIC is better, so it is clear that time-based correlation

structure is far superior to dose-based. We will used the second

model for the remainder of the analysis. But first we check some of

the model assumptions.

`r ipacue()`

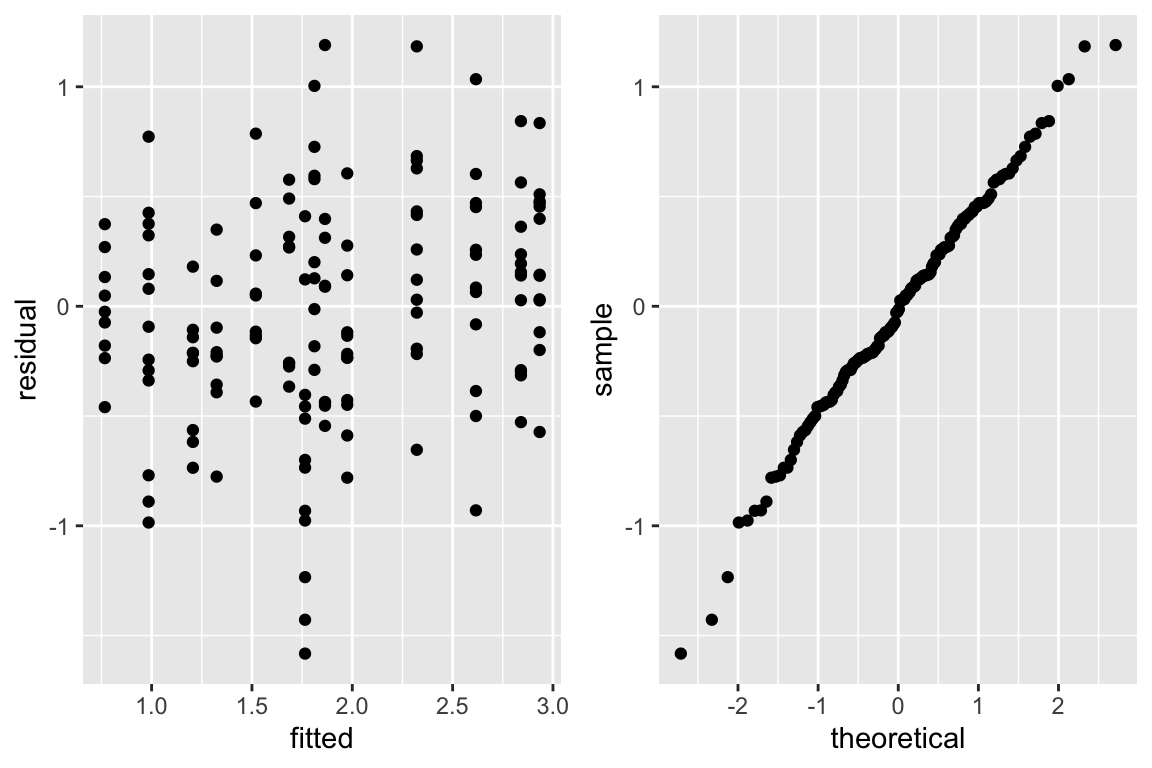

```{r glsc,w=6,h=4,cap='Checking assumptions of the GLS model that is linear after logging dose and blood flow. The graph on the right is a QQ-plot to check normality of the residuals from the model, where linearity implies normality.',scap='Checking assumptions of GLS model'}

#| label: fig-serial-glsc

w <- data.frame(residual=resid(b), fitted=fitted(b))

p1 <- ggplot(w, aes(x=fitted, y=residual)) + geom_point()

p2 <- ggplot(w, aes(sample=residual)) + stat_qq()

gridExtra::grid.arrange(p1, p2, ncol=2)

```

`r ipacue()`

The test for dose $\times$ race interaction in the above ANOVA summary of Wald statistics shows strong evidence for difference in curve

characteristics across races. This test agrees in magnitude

with the less parametric approach using the logistic model above. But

the logistic model also tests for an overall shift in distributions

due to race, and the more efficient test for the combined race main

effect and dose interaction effect from GLS is more significant

with a Wald $\chi^{2}_{2} = 32.45$^[The $\chi^2$ for race with the dose-based correlation structure was a whopping 100 indicating that lack of fit of the correlation structure can have a significant effect on the rest of the GLS model.]. The

estimate of the correlation between two log blood flows measured on

the same subject one time unit apart is 0.69.

The equal variance and normality assumptions appear to be well met as

judged by @fig-serial-glsc.

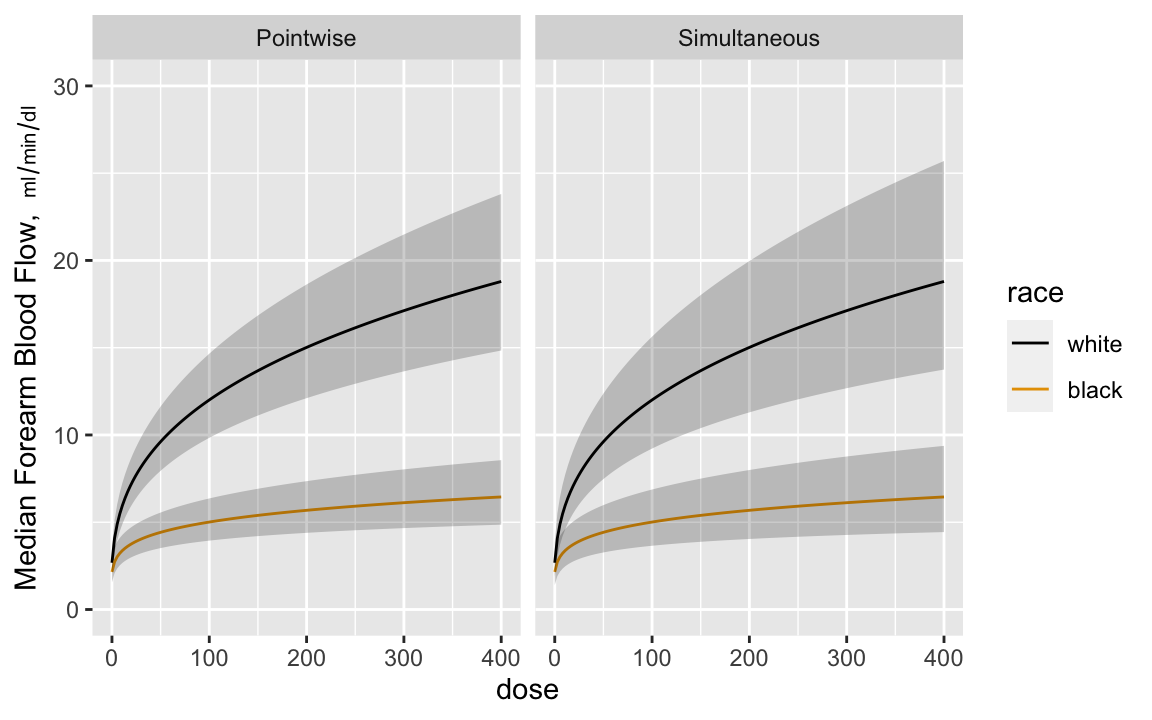

`r mrg(sound("serial-7"))`

Now estimate the dose-response curves by race, with pointwise confidence intervals and simultaneous intervals that allow one to make

statements about the entire curves^[Since the model is linear in log dose there are two parameters involving dose---the dose main effect and the race $\times$ dose interaction effect. The simultaneous inference adjustment only needs to reflect simultaneity in two dimensions.]. Anti-log the predicted values to

get predictions on the original blood flow scale. Anti-logging

predictions from a model that assumes a normal distribution on the

logged values results in estimates of the median response. `r ipacue()`

```{r glsd,w=6,h=3.75,cap='Pointwise and simultaneous confidence bands for median dose-response curves by race',scap='Confidence bands for median dose-response curves',cache=TRUE}

#| label: fig-serial-glsd

dos <- seq(0, 400, length=150)

p <- Predict(b, dose=dos, race, fun=exp)

s <- Predict(b, dose=dos, race, fun=exp, conf.type='simultaneous')

ps <- rbind(Pointwise=p, Simultaneous=s)

ggplot(ps, ylab=expression(paste('Median Forearm Blood Flow, ',

scriptstyle(ml/min/dl))))

```

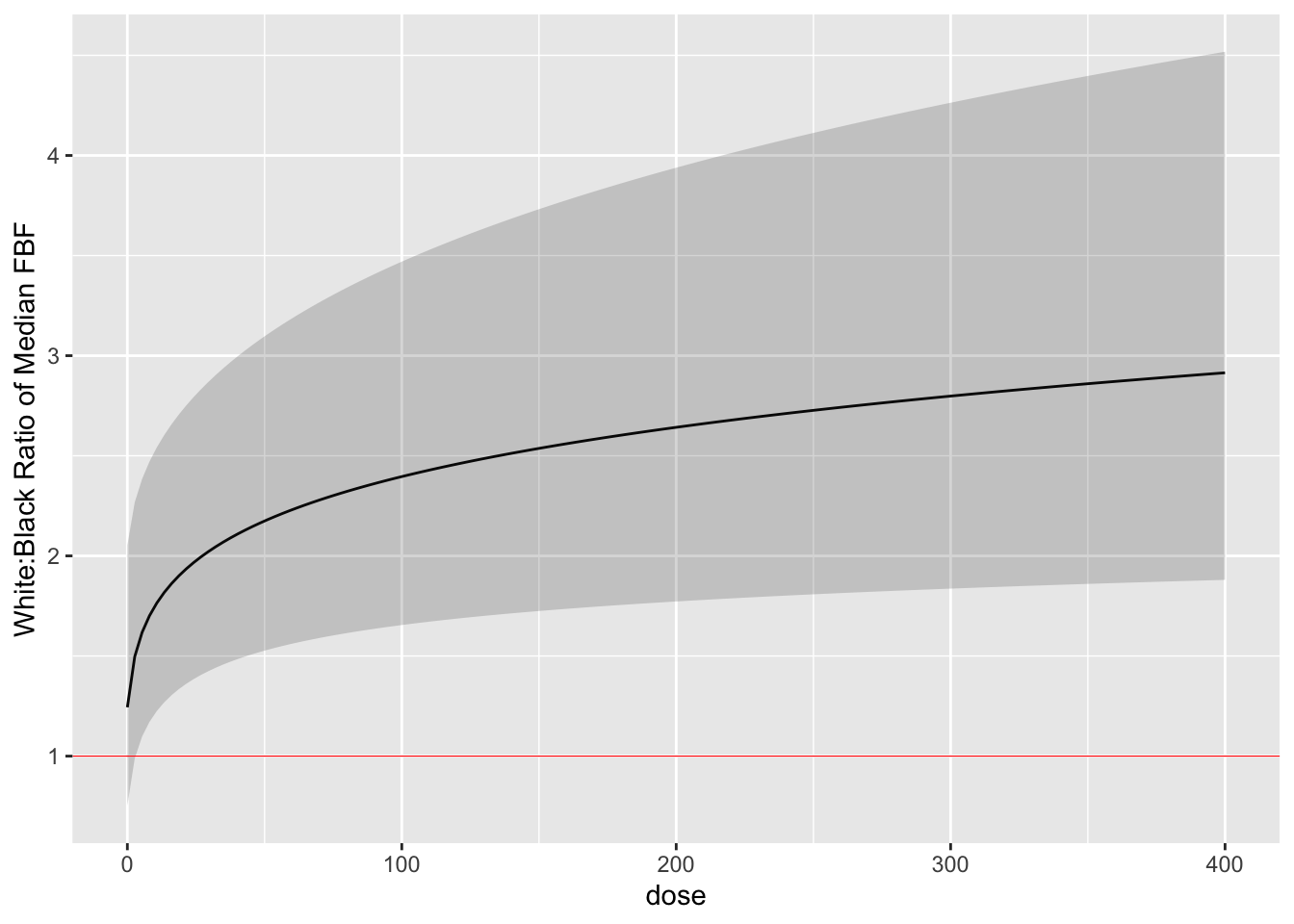

Finally we estimate the white:black fold change (ratio of medians) as

a function of dose with simultaneous confidence bands. `r ipacue()`

```{r glse,cap='White:black fold change for median response as a function of dose, with simultaneous confidence band',cache=TRUE}

#| label: fig-serial-glse

k <- contrast(b, list(dose=dos, race='white'),

list(dose=dos, race='black'), conf.type='simultaneous')

k <- as.data.frame(k[c('dose', 'Contrast', 'Lower', 'Upper')])

ggplot(k, aes(x=dose, y=exp(Contrast))) + geom_line() +

geom_ribbon(aes(ymin=exp(Lower), ymax=exp(Upper)), alpha=0.2, linetype=0,

show_guide=FALSE) +

geom_hline(yintercept=1, col='red', size=.2) +

ylab('White:Black Ratio of Median FBF')

```

By comparing the simultaneous confidence binds to the red horizontal

line, one can draw the inference that the dose-response for blacks is

everywhere different than that for whites when the dose exceeds zero.

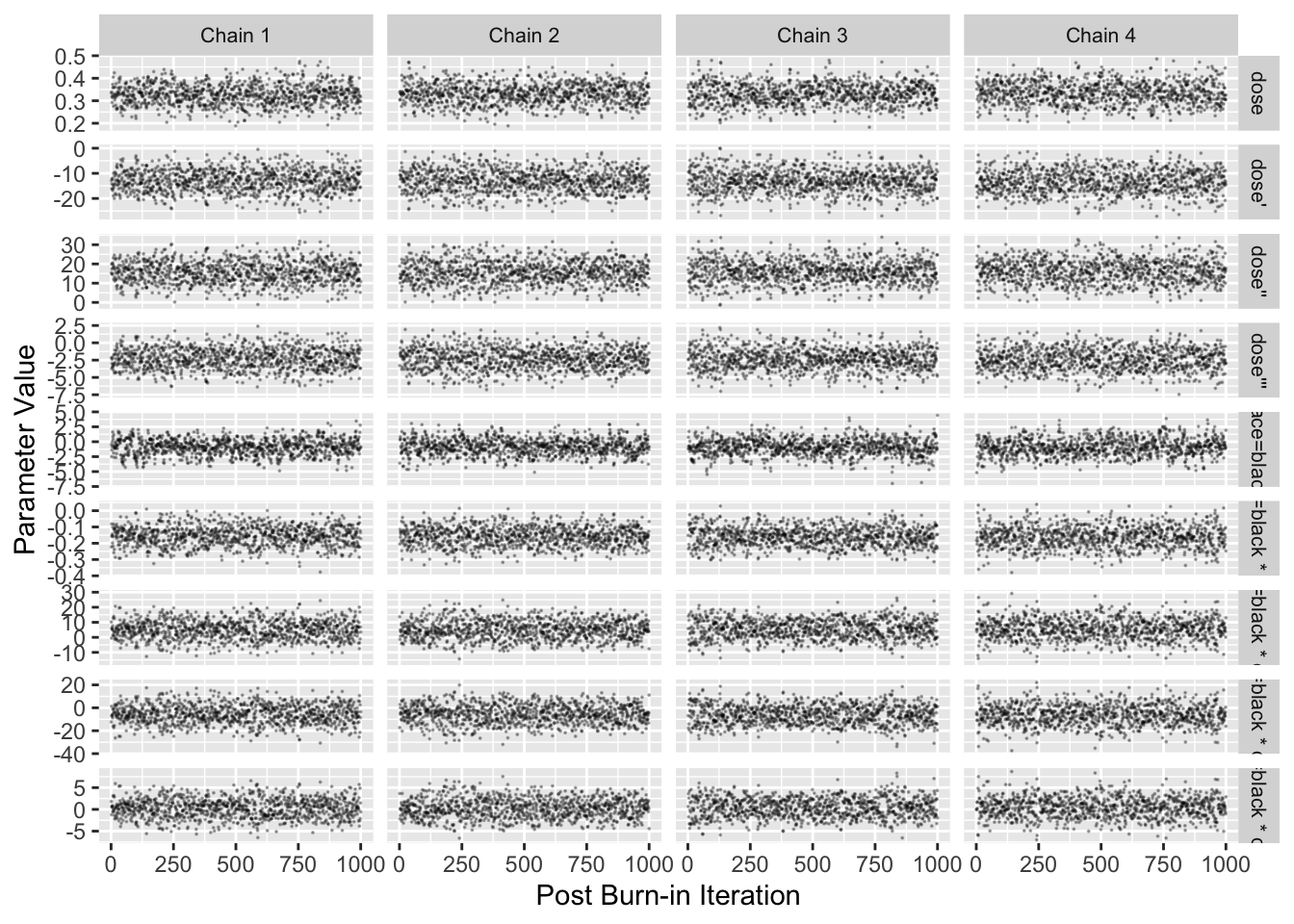

### Longitudinal Bayesian Mixed Effects Semiparametric Model

* Proportional odds model with random effects

* Robust with regard to distribution

* Compound symmetry may not be realistic

* Model estimates logits of exceedance probabilities

* Convert these to means on the original scale

```{r blrm,cap='Stan Hamiltonion MCMC convergence diagnostics for non-intercepts',cap='MCMC diagnostics'}

#| label: fig-serial-blrm

require(rmsb)

# Use cmdstan instead of rstan to get more current methods and

# better performance

options(mc.cores = parallel::detectCores() - 1, rmsb.backend='cmdstan')

cmdstanr::set_cmdstan_path(cmdstan.loc)

b <- blrm(fbf ~ race * rcs(dose, 5) + cluster(id), data=d)

b

stanDxplot(b)

```

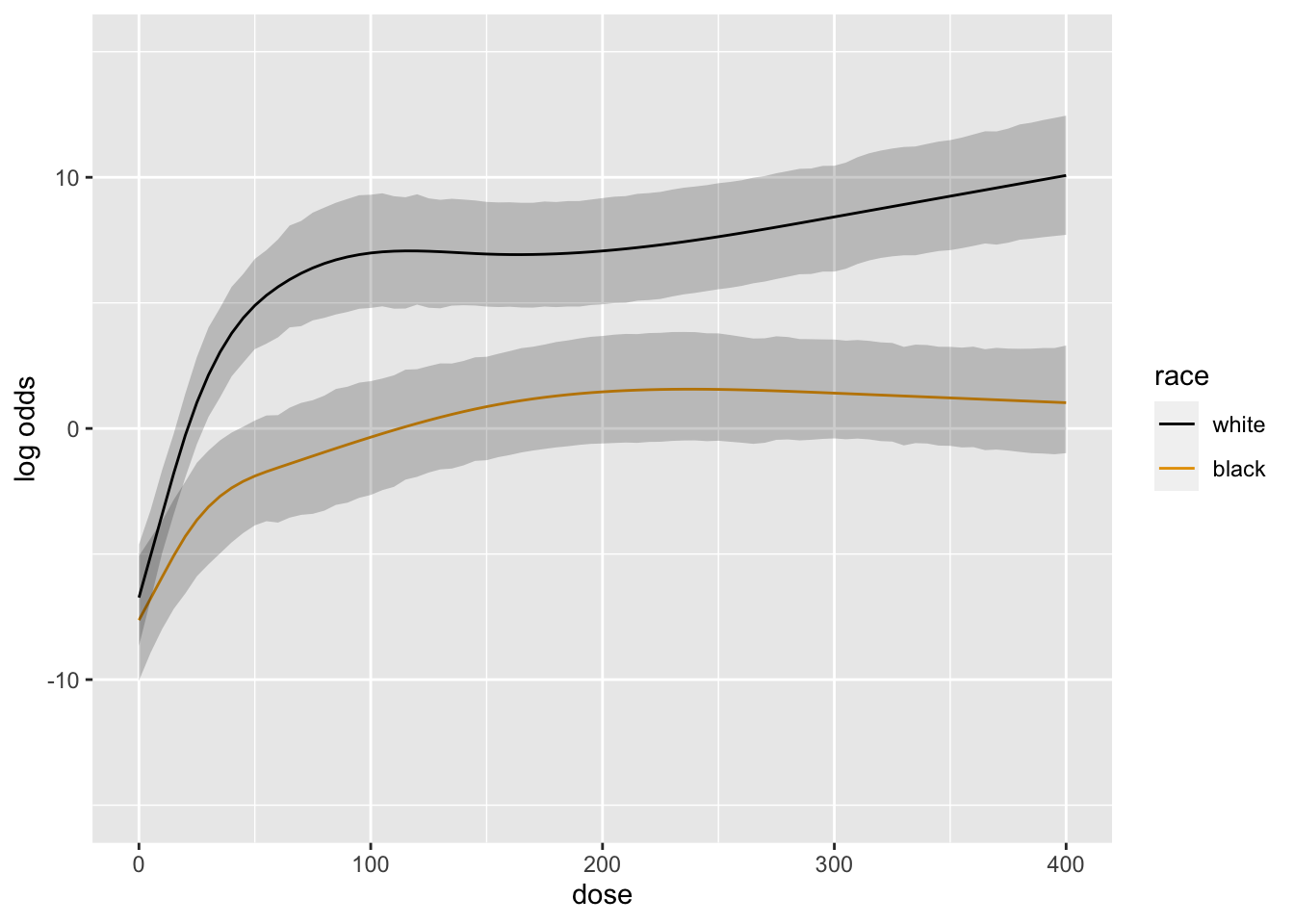

```{r blrm2,cap='Posterior mean logit of exceedance probability', scap='Posterior mean logit'}

#| label: fig-serial-blrm2

doses <- seq(0, 400, by=5)

ggplot(Predict(b, dose=doses, race))

```

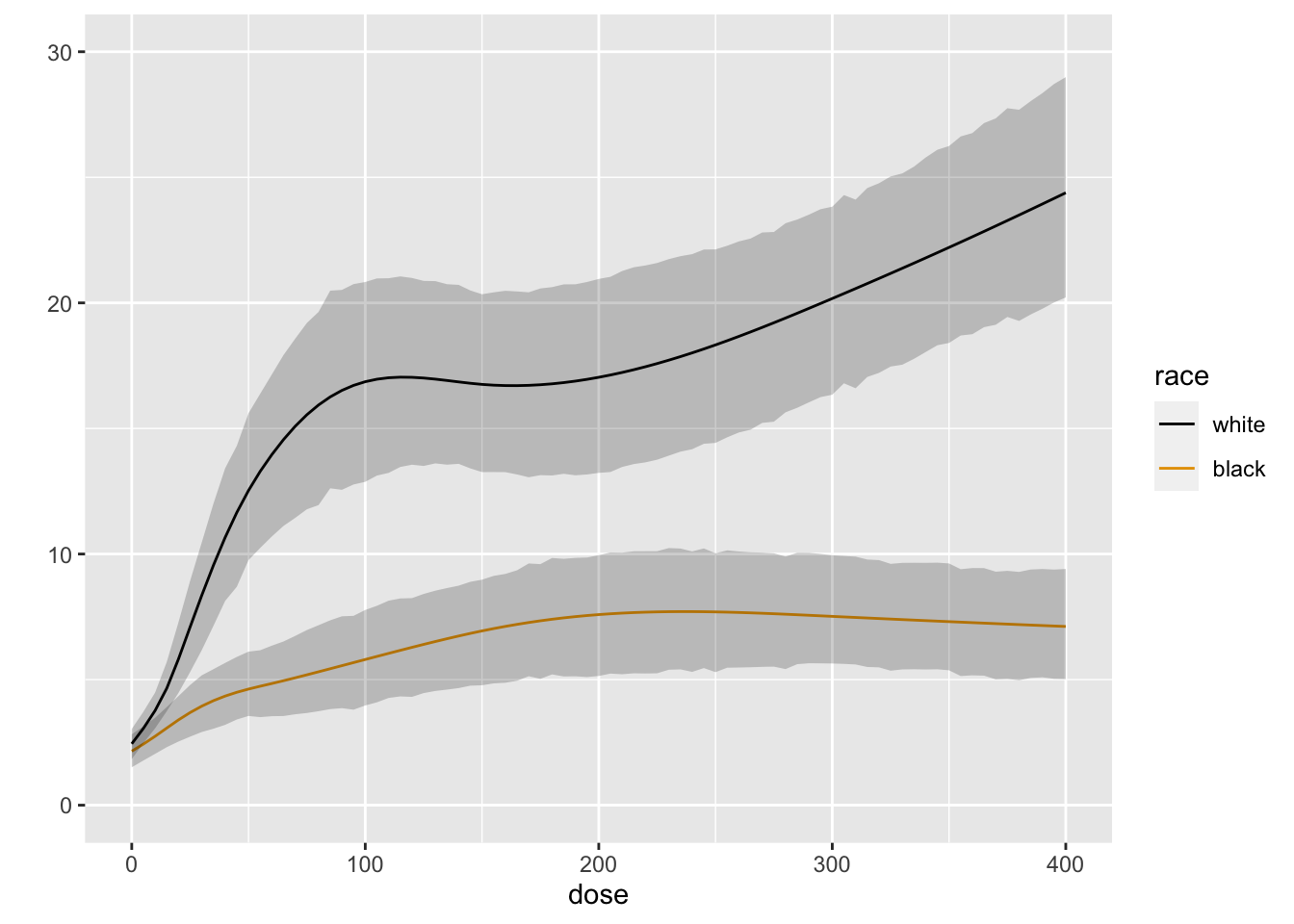

```{r blrm3,cap='Posterior mean of true mean forearm blood flow',scap='Posterior mean for mean blood flow'}

#| label: fig-serial-blrm3

M <- Mean(b)

ggplot(Predict(b, dose=doses, race, fun=M))

k <- contrast(b, list(race='white', dose=seq(0, 400, by=100)),

list(race='black', dose=seq(0, 400, by=100)))

k

```

```{r echo=FALSE}

saveCap('15')

```