```{r include=FALSE}

require(Hmisc)

require(qreport)

options(qproject='rms', prType='html')

getRs('qbookfun.r')

hookaddcap()

knitr::set_alias(w = 'fig.width', h = 'fig.height', cap = 'fig.cap', scap ='fig.scap')

```

# Case Study in Data Reduction {#sec-impred}

Recall that the aim of data reduction is to reduce (without using the

outcome) the number of parameters needed in the outcome model.

The following case study illustrates these techniques:

1. redundancy analysis;

1. variable clustering;

1. data reduction using principal component analysis (PCA), sparse

PCA, and pre\-transformations;

1. restricted cubic spline fitting using ordinary least squares,

in the context of scaling; and

1. scaling/variable transformations using canonical variates

and nonparametric additive regression.

## Data

Consider the 506-patient \index{datasets!prostate}prostate cancer

dataset from @bya80cho. The data are listed

in [@data; Table 46] and are

available at <https://hbiostat.org/data>.

These data were from a randomized trial comparing four treatments for

stage 3 and 4 prostate cancer, with

almost equal numbers of patients on placebo and each of three doses of

estrogen. Four patients had missing values on all of the following

variables:

`wt, pf, hx, sbp, dbp, ekg, hg, bm`; two of these patients were

also missing `sz`. These patients are excluded from

consideration. The ultimate goal of an analysis of the dataset might

be to discover patterns in survival or to do an analysis of covariance

to assess the effect of treatment while adjusting for patient

heterogeneity. See Chapter @sec-coxcase for such analyses.

The data reductions developed here are

general and can be used for a variety of dependent variables.

The variable names, labels, and a summary of the data are printed below. Because of extreme skewness, `ap` is log-transformed for the purpose of making its spike histogram.

```{r results='asis'}

require(Hmisc)

getHdata(prostate) # Download and make prostate accessible

# Convert an old date format to R format

prostate$sdate <- as.Date(prostate$sdate)

d <- describe(prostate[2:17],

trans=list(ap=list('log', log, exp)))

sparkline::sparkline(0) # load sparkline javascript dependencies

maketabs(print(d, 'both'), initblank=TRUE, wide=TRUE)

```

`stage` is defined by `ap` as well as X-ray results. Of the

patients in stage 3, 0.92 have `ap` $\leq$ 0.8. Of those in stage 4,

0.93 have `ap` > 0.8. Since `stage` can be predicted almost

certainly from `ap`, we do not consider `stage` in some of the

analyses.

## How Many Parameters Can Be Estimated?

There are 354 deaths among the 502 patients. If predicting survival

time were of major interest, we could develop a reliable

model if no more than about $354/15 = 24$ parameters

were _examined_ against $Y$ in unpenalized modeling. Suppose that

a full model with no

interactions is fitted and that linearity is not assumed for any

continuous predictors. Assuming `age` is almost linear, we could

fit a restricted cubic spline function with three knots. For the other

continuous variables, let us use five knots. For categorical predictors,

the maximum number of degrees of freedom needed would be one fewer than

the number of categories. For `pf` we could lump the last two

categories since the last category has only 2 patients. Likewise, we

could combine the last two levels of `ekg`.

@tbl-impred-maxdf lists candidate

predictors with the maximum number of parameters we consider for each.

| Predictor: | `rx` | `age` | `wt` | `pf` | `hx` | `sbp` | `dbp` | `ekg` | `hg` | `sz` | `sg` | `ap` | `bm` |

|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----|-----|

| Number of Parameters: | 3 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

: Degrees of freedom needed for predictors {#tbl-impred-maxdf}

## Redundancy Analysis

As described in Section @sec-multivar-redun, it is occasionally useful to

do a rigorous redundancy analysis on a set of potential predictors.

Let us run the algorithm discussed there, on the set of predictors we

are considering. We will use a low threshold (0.3) for $R^2$ for

demonstration purposes.

```{r}

# Allow only 1 d.f. for three of the predictors

prostate <-

transform(prostate,

ekg.norm = 1*(ekg %in% c("normal","benign")),

rxn = as.numeric(rx),

pfn = as.numeric(pf))

# Force pfn, rxn to be linear because of difficulty of placing

# knots with so many ties in the data

# Note: all incomplete cases are deleted (inefficient)

r <- redun(~ stage + I(rxn) + age + wt + I(pfn) + hx +

sbp + dbp + ekg.norm + hg + sz + sg + ap + bm,

r2=.3, type='adjusted', data=prostate)

r

r2describe(r$scores, nvmax=4) # show strongest predictors of each variable

```

By any reasonable criterion on $R^2$, none of the predictors is

redundant. `stage` can be predicted with an $R^{2} = 0.658$ from

the other 13 variables, but only with $R^{2} = 0.493$ after deletion

of 3 variables later declared to be "redundant."

## Variable Clustering

From @tbl-impred-maxdf, the total number of parameters is

42, so some data reduction should be

considered. We resist the temptation to take the "easy way out"

using stepwise variable selection so that we can achieve a more stable

modeling process ^[@sau92boo used the bootstrap to demonstrate the variability of a standard variable selection procedure for the prostate cancer dataset.] and obtain

unbiased standard errors. Before using a variable

clustering procedure, note that `ap` is extremely skewed. To

handle skewness, we use Spearman rank correlations for continuous

variables (later we transform each variable using

`transcan`, which will allow ordinary correlation coefficients to

be used). After classifying `ekg` as "normal/benign" versus

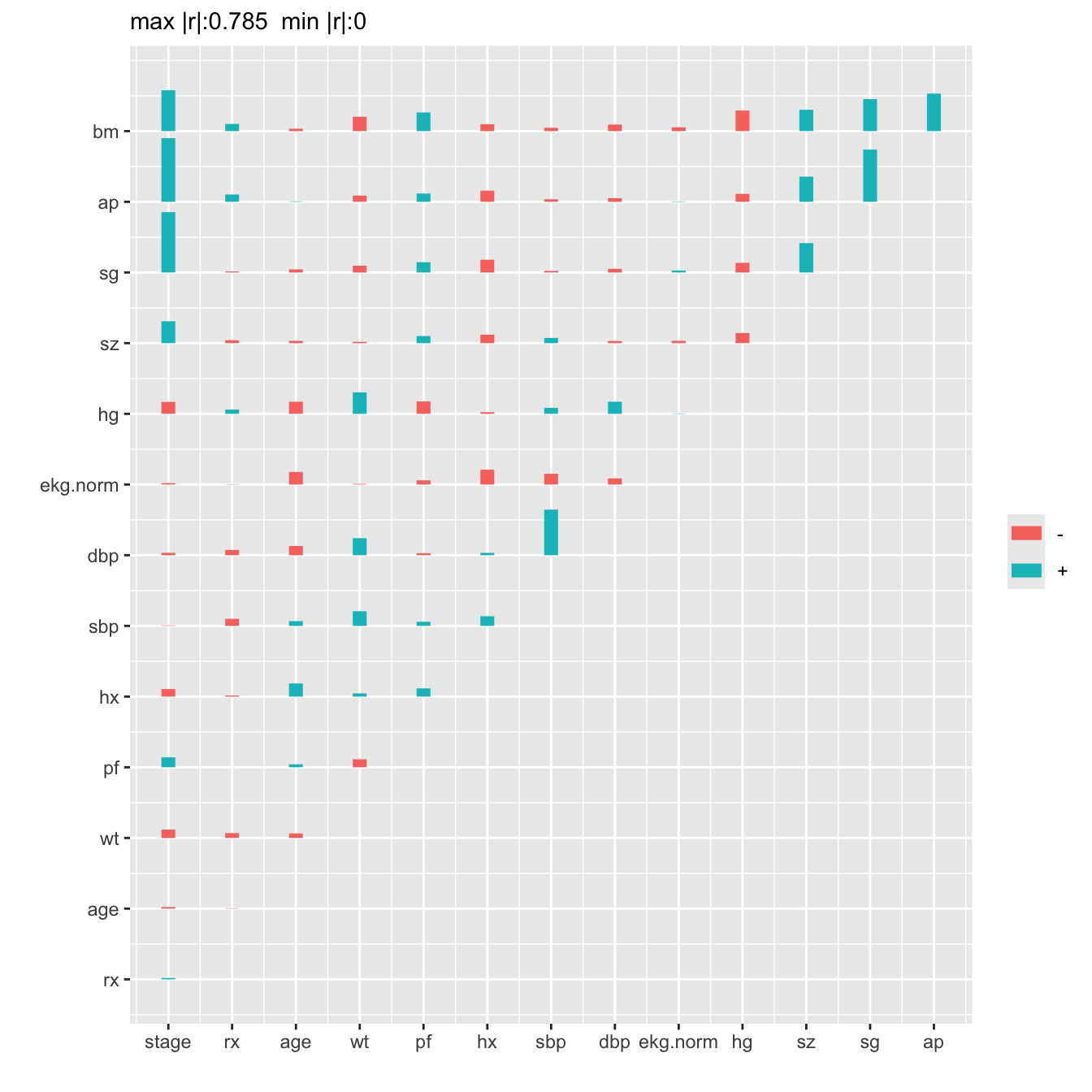

everything else, the Spearman correlations are plotted below.

```{r}

x <- with(prostate,

cbind(stage, rx, age, wt, pf, hx, sbp, dbp,

ekg.norm, hg, sz, sg, ap, bm))

# If no missing data, could use cor(apply(x, 2, rank))

r <- rcorr(x, type="spearman")$r # rcorr in Hmisc

maxabsr <- max(abs(r[row(r) != col(r)]))

```

```{r spearman,h=7,w=7,cap='Matrix of Spearman $\\rho$ rank correlation coefficients between predictors. Horizontal gray scale lines correspond to $\\rho=0$. The tallest bar corresponds to $|\\rho|=0.785$.',scap='Spearman $\\rho$ rank correlations of predictors'}

#| label: fig-impred-spearman

plotCorrM(r)[[1]] # An Hmisc function

```

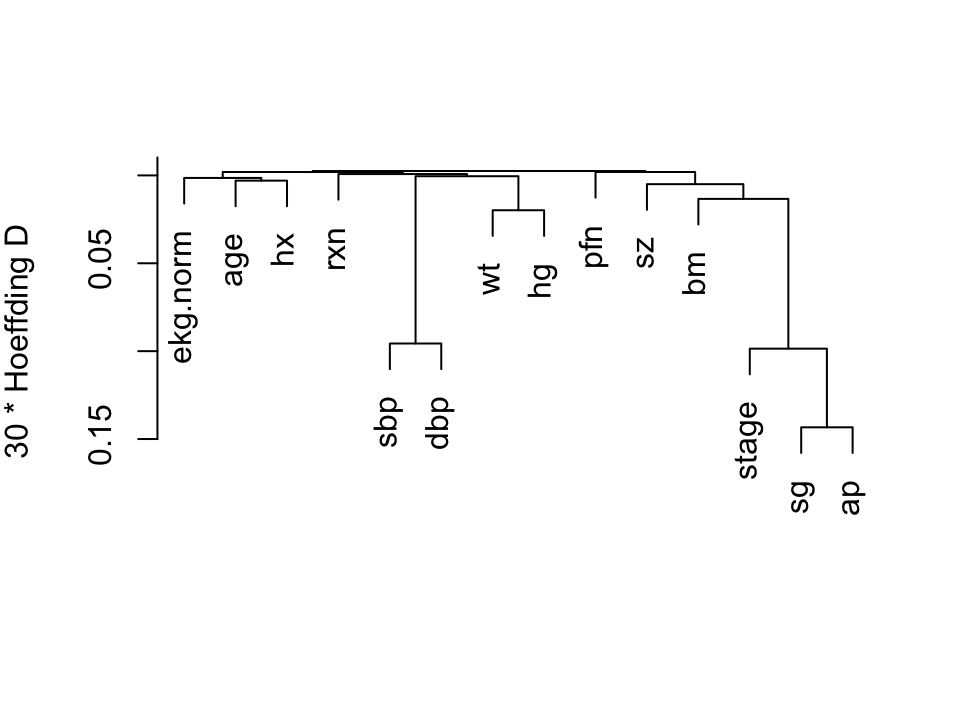

We perform a hierarchical

cluster analysis based on a similarity matrix that contains pairwise

Hoeffding $D$ statistics [@hoe48non] $D$ will detect

nonmonotonic associations.

```{r hclust,h=3.75,w=5,cap="Hierarchical clustering using Hoeffding's $D$ as a similarity measure. Dummy variables were used for the categorical variable `ekg. Some of the dummy variables cluster together since they are by definition negatively correlated.",scap="'Hierarchical clustering"}

#| label: fig-impred-hclust

vc <- varclus(~ stage + rxn + age + wt + pfn + hx +

sbp + dbp + ekg.norm + hg + sz + sg + ap + bm,

sim='hoeffding', data=prostate)

plot(vc)

```

We combine `sbp` and `dbp`, and tentatively combine

`ap, sg, sz`, and `bm`.

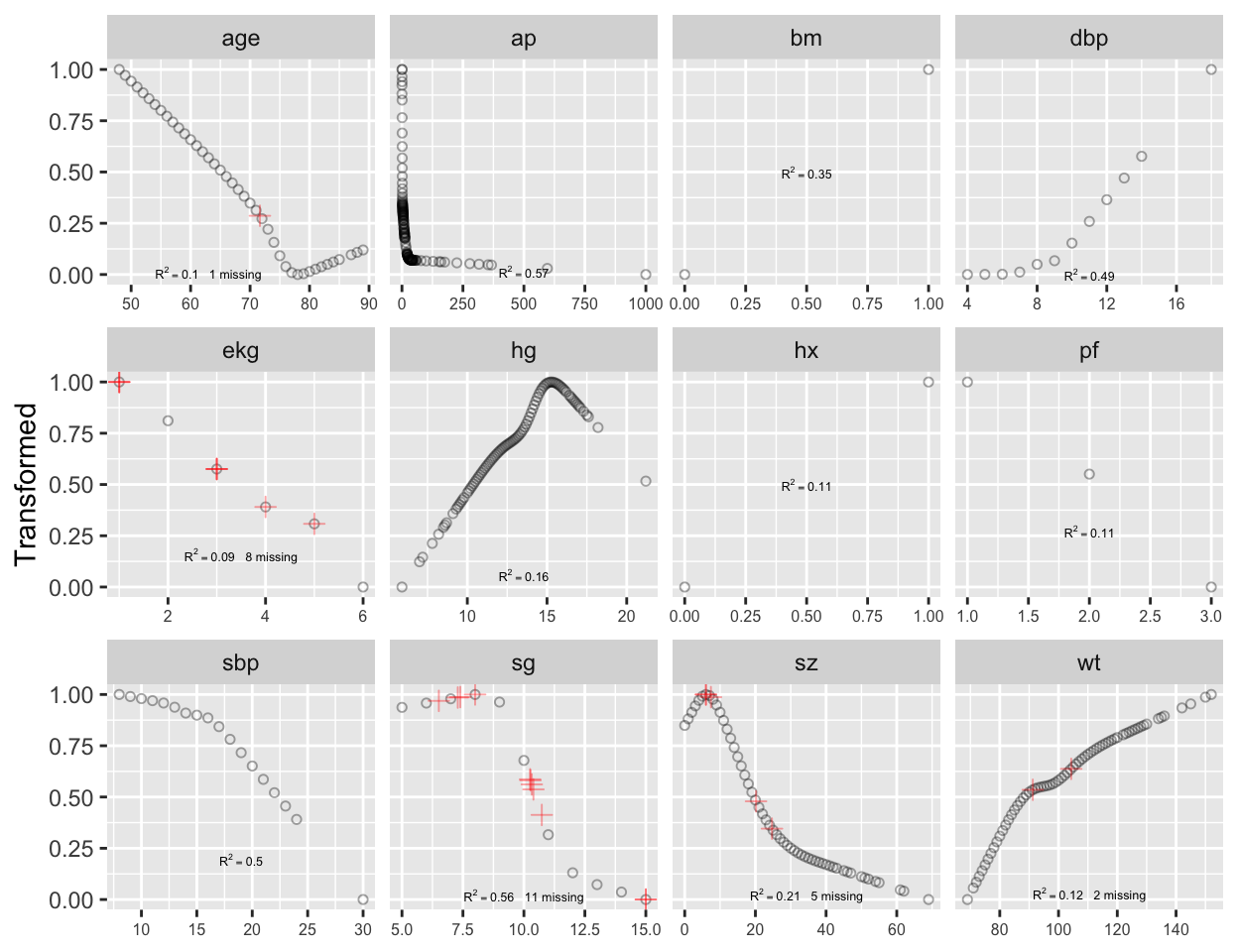

## Transformation and Single Imputation Using `transcan` {#sec-impred-transcan}

Now we turn to the scoring of the predictors to potentially reduce the

number of regression parameters that are needed later by doing away

with the need for nonlinear terms and multiple dummy variables.

The `R` `Hmisc` package `transcan` function

defaults to using a maximum generalized variance

method [@prinqual] that incorporates canonical variates to

optimally transform both sides of a multiple regression model. Each

predictor is treated in turn as a variable being predicted, and all

variables are expanded into restricted cubic splines (for continuous variables) or dummy variables (for categorical ones).

```{r transcan,w=6.5,h=5,cap='Simultaneous transformation and single imputation of all candidate predictors using `transcan`. Imputed values are shown as red plus signs. Transformed values are arbitrarily scaled to $[0,1]$.',scap='Simultaneous transformation and imputation using `transcan`'}

#| label: fig-impred-transcan

spar(bot=1)

# Combine 2 levels of ekg (one had freq. 1)

levels(prostate$ekg)[levels(prostate$ekg) %in%

c('old MI', 'recent MI')] <- 'MI'

prostate$pf.coded <- as.integer(prostate$pf)

# make a numeric version; combine last 2 levels of original

levels(prostate$pf) <- levels(prostate$pf)[c(1,2,3,3)]

ptrans <-

transcan(~ sz + sg + ap + sbp + dbp +

age + wt + hg + ekg + pf + bm + hx, imputed=TRUE,

transformed=TRUE, trantab=TRUE, pl=FALSE,

show.na=TRUE, data=prostate, frac=.1, pr=FALSE)

summary(ptrans, digits=4)

ggplot(ptrans, scale=TRUE) +

theme(axis.text.x=element_text(size=6))

```

Note that at face value the transformation of `ap` was derived in a

circular manner,

since the combined index of stage and histologic grade, `sg`,

uses in its stage component a cutoff on `ap`. However, if `sg`

is omitted from consideration, the resulting transformation for `ap`

does not change appreciably. Note that `bm` and `hx` are

represented as binary variables, so their coefficients in the table of

canonical variable coefficients

are on a different scale. For the variables that were actually transformed,

the coefficients are for standardized transformed variables (mean 0,

variance 1). From examining the $R^2$s,

`age, wt, ekg, pf`, and `hx` are not

strongly related to other variables. Imputations for `age, wt, ekg`

are thus relying more on the median or modal values from the marginal

distributions.

From the coefficients of first (standardized) canonical variates,

`sbp` is predicted almost solely from `dbp`; `bm` is

predicted mainly from `ap, hg`, and `pf`. ^[@sch97pro used logistic models to impute dichotomizations of the predictors for this dataset.]

## Data Reduction Using Principal Components {#sec-impred-pc}

The first PC, PC$_{1}$, is the linear combination of standardized

variables having maximum variance. PC$_{2}$ is the linear

combination of predictors having the second largest variance such that

PC$_{2}$ is orthogonal to (uncorrelated with) PC$_{1}$. If there are

$p$ raw variables, the first $k$ PCs, where $k < p$, will explain only

part of the variation in the whole system of $p$ variables unless one

or more of the original variables is exactly a linear combination of

the remaining variables. Note that it is common to scale and center

variables to have mean zero and variance 1 before computing PCs.

The response variable (here, time until death due to any cause) is not

examined during data reduction, so that if PCs are selected by

variance explained in the $X$-space and not by variation explained in

$Y$, one needn't correct for model uncertainty or multiple comparisons.

PCA results in data reduction when the analyst uses only a subset of

the $p$ possible PCs in predicting $Y$. This is called

_incomplete principal component regression_.

When one sequentially enters PCs into a predictive model in a strict

pre-specified order (i.e., by descending amounts of variance explained

for the system of $p$ variables), model uncertainty requiring

bootstrap adjustment is minimized. In contrast, model uncertainty associated

with stepwise regression (driven by associations with $Y$) is massive.

For the prostate dataset, consider PCs

on raw candidate predictors, expanding polytomous factors using indicator variables.

The `R` function `princmp` is used, after singly imputing missing raw

values using `transcan`'s optimal additive nonlinear models. In

this series of analyses we ignore the treatment variable, `rx`. `princmp` calls the built-in `princomp` function. `princmp` assists with interpretation of PCs.

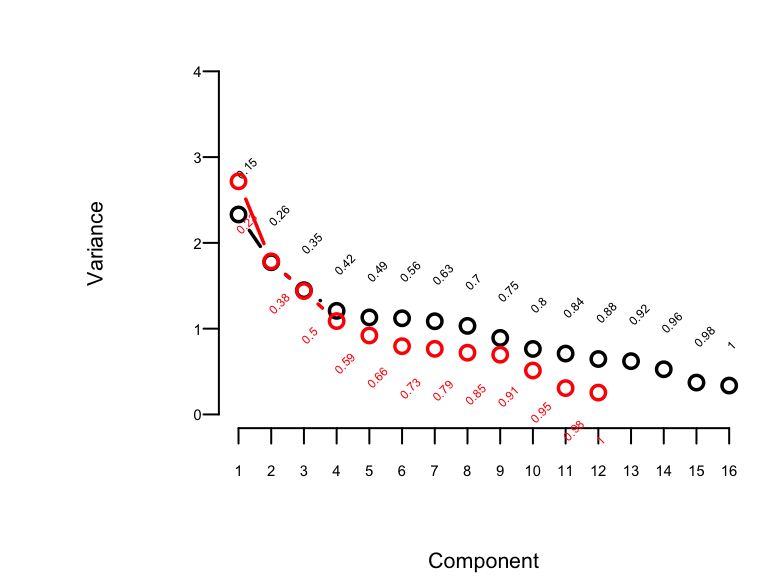

```{r pc,w=4,h=3,cap='Variance of the system of raw predictors (black) explained by individual principal components (lines) along with cumulative proportion of variance explained (text), and variance explained by components computed on `transcan`-transformed variables (red)',scap='Variance of the system explained by principal components.'}

#| label: fig-impred-pc

#| fig.width: 7

#| column: page-inset-right

spar(top=1, ps=7)

# Impute all missing values in all variables given to transcan

imputed <- impute(ptrans, data=prostate, list.out=TRUE)

imputed <- as.data.frame(imputed)

# Compute principal components on imputed data. princmp will expand

# the categorical variable EKG into indicator variables.

# Use correlation matrix

pfn <- prostate$pfn

prin.raw <- princmp(~ sz + sg + ap + sbp + dbp + age +

wt + hg + ekg + pfn + bm + hx,

k=16, sw=TRUE, data=imputed)

prin.raw

plot(prin.raw, ylim=c(0,4), offset=1)

prin.trans <- princmp(ptrans$transformed, k=12)

prin.trans

plot(prin.trans, add=TRUE, col='red', offset=-1.3)

```

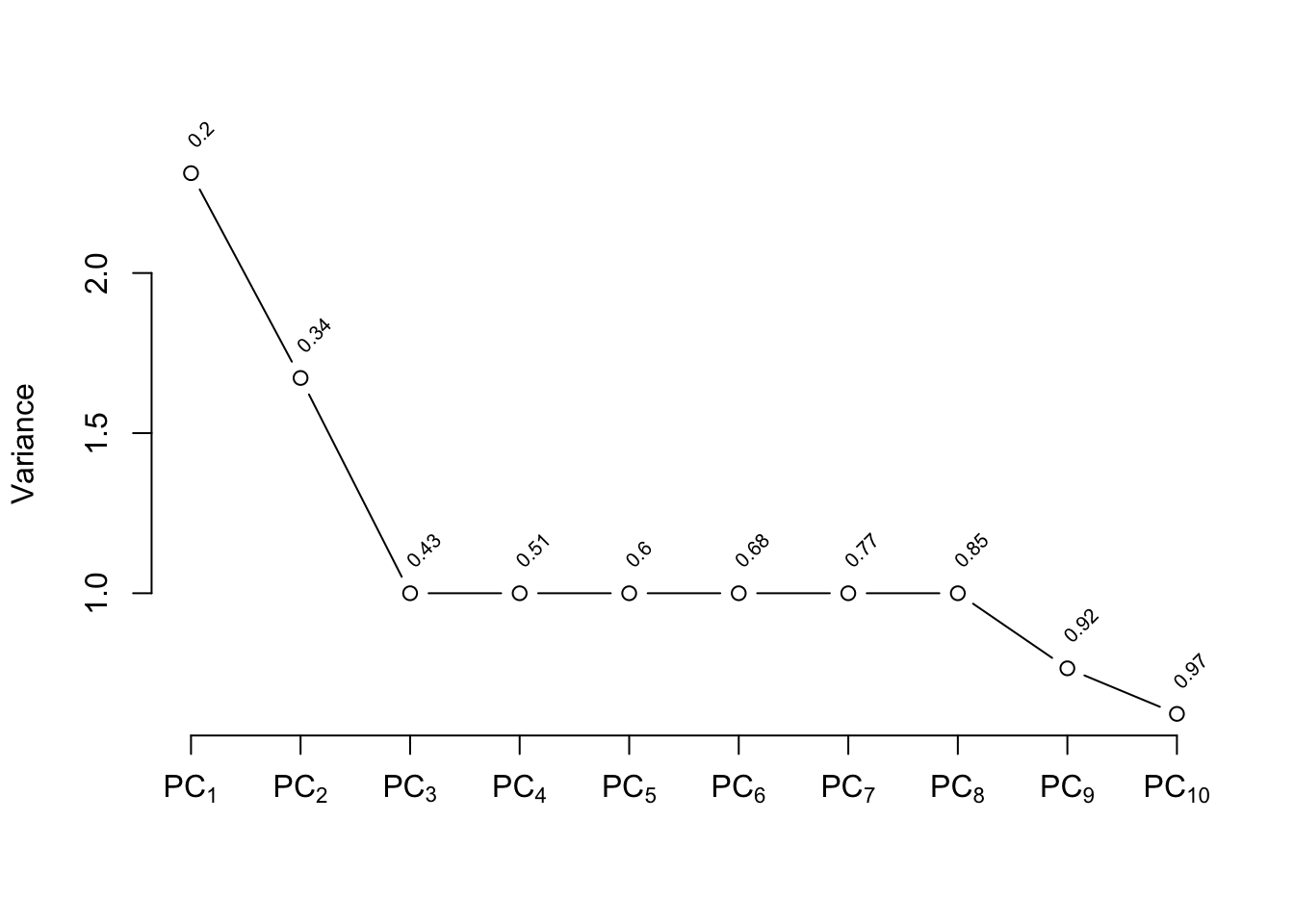

The plot shown in @fig-impred-pc is called a

"scree" plot [@jol10pri; pp. 96--99, 104, 106]. It shows the variation

explained by the first $k$ principal components as $k$ increases all

the way to 16 parameters (no data reduction). It requires 10

of the 16 possible components to explain $> 0.8$ of the variance,

and the first 5 components explain $0.49$ of the variance of the

system. Two of the 16 dimensions are almost totally redundant.

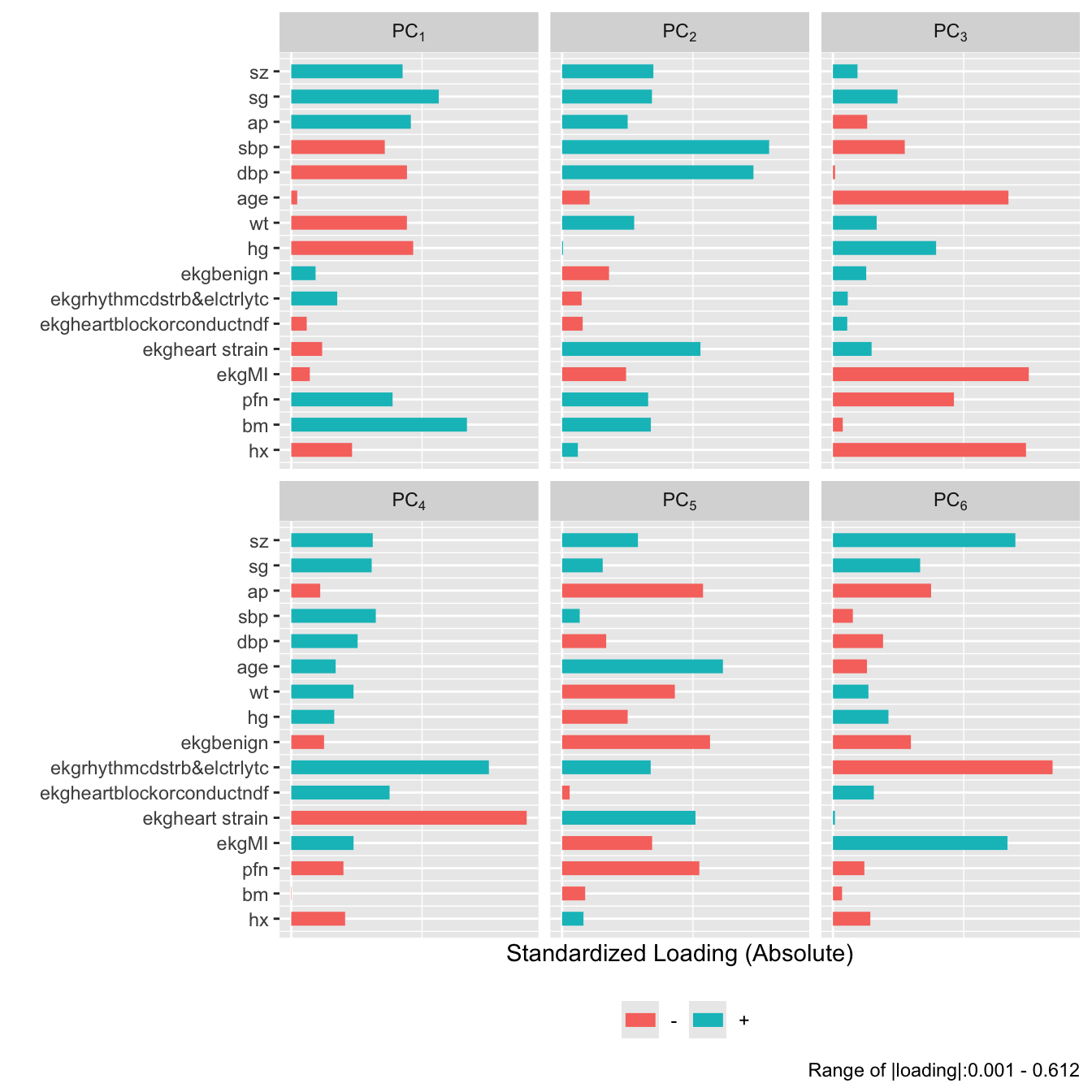

```{r}

#| fig-height: 7

plot(prin.raw, 'loadings', k=6)

```

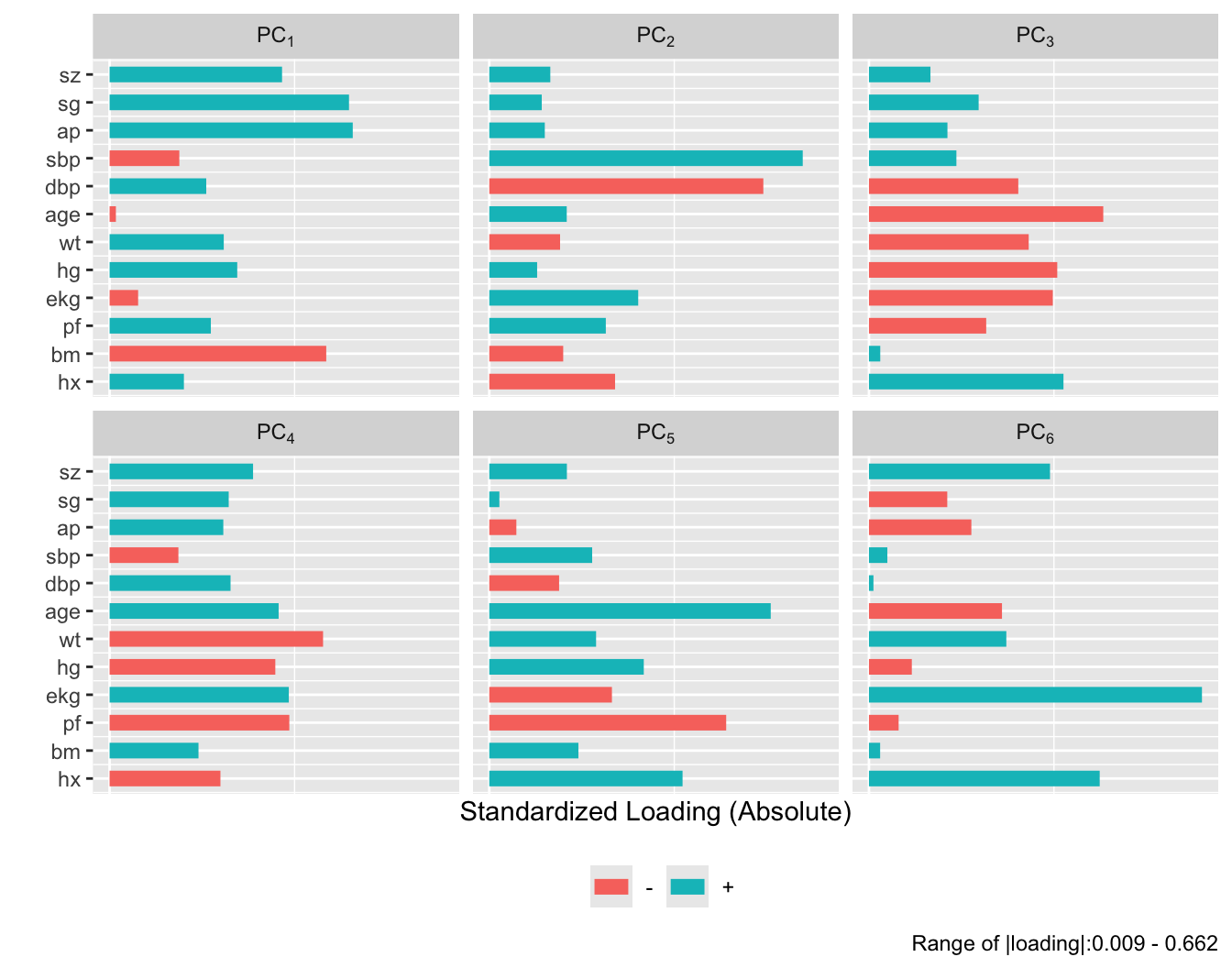

```{r}

#| fig-height: 5.5

plot(prin.trans, 'loadings', k=6)

```

After repeating this process when transforming all predictors via

`transcan`, we have only 12 degrees of freedom for the 12

predictors. The variance explained is depicted in @fig-impred-pc in red.

It requires at least 8 of the 12 possible components to explain $\geq 0.8$

of the variance, and the first 5 components explain $0.66$ of the

variance as opposed to $0.49$ for untransformed variables.

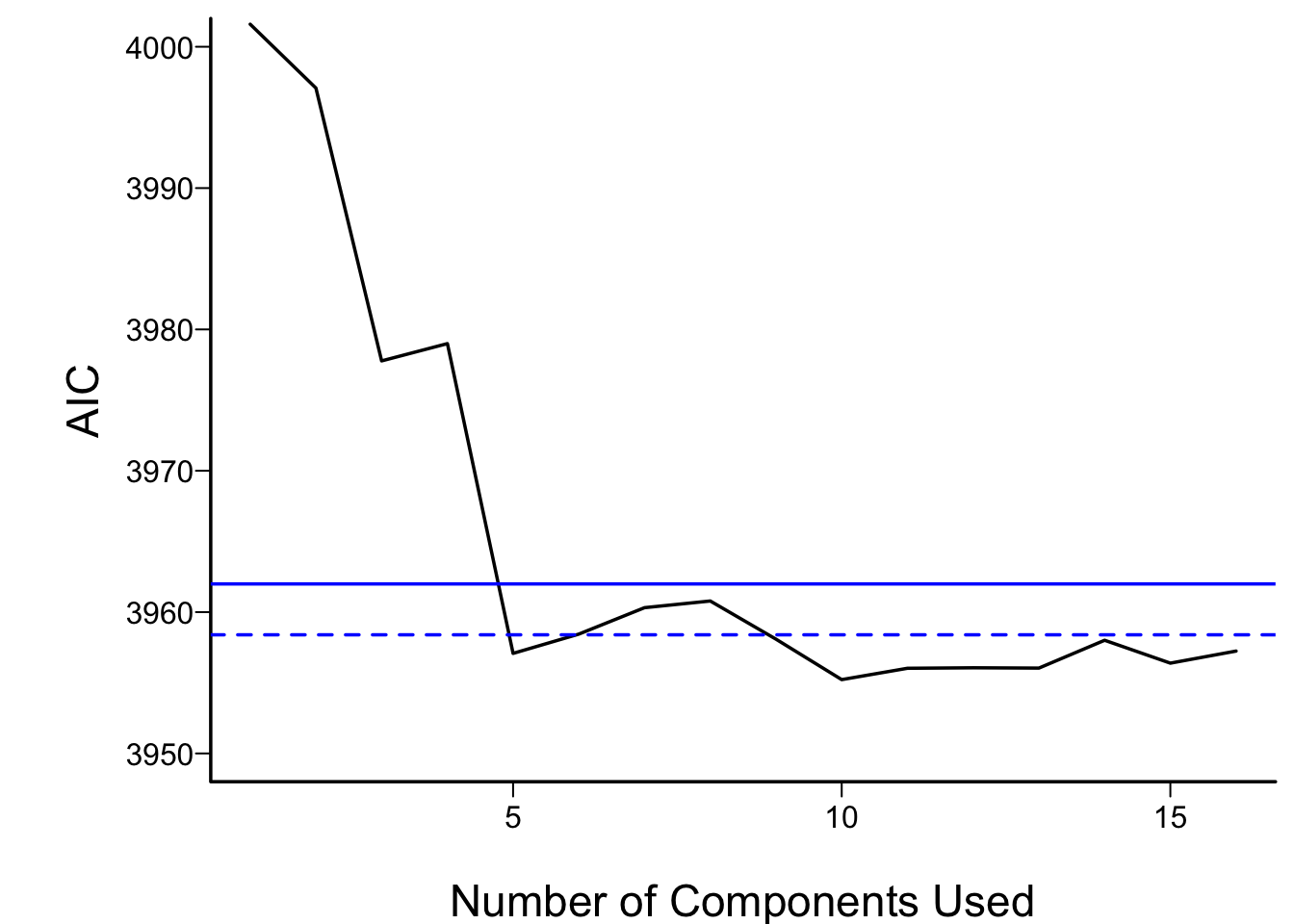

Let us see how the PCs "explain" the times until death using the

Cox regression [@cox72reg] function from `rms`, `cph`, described in

@sec-cox.

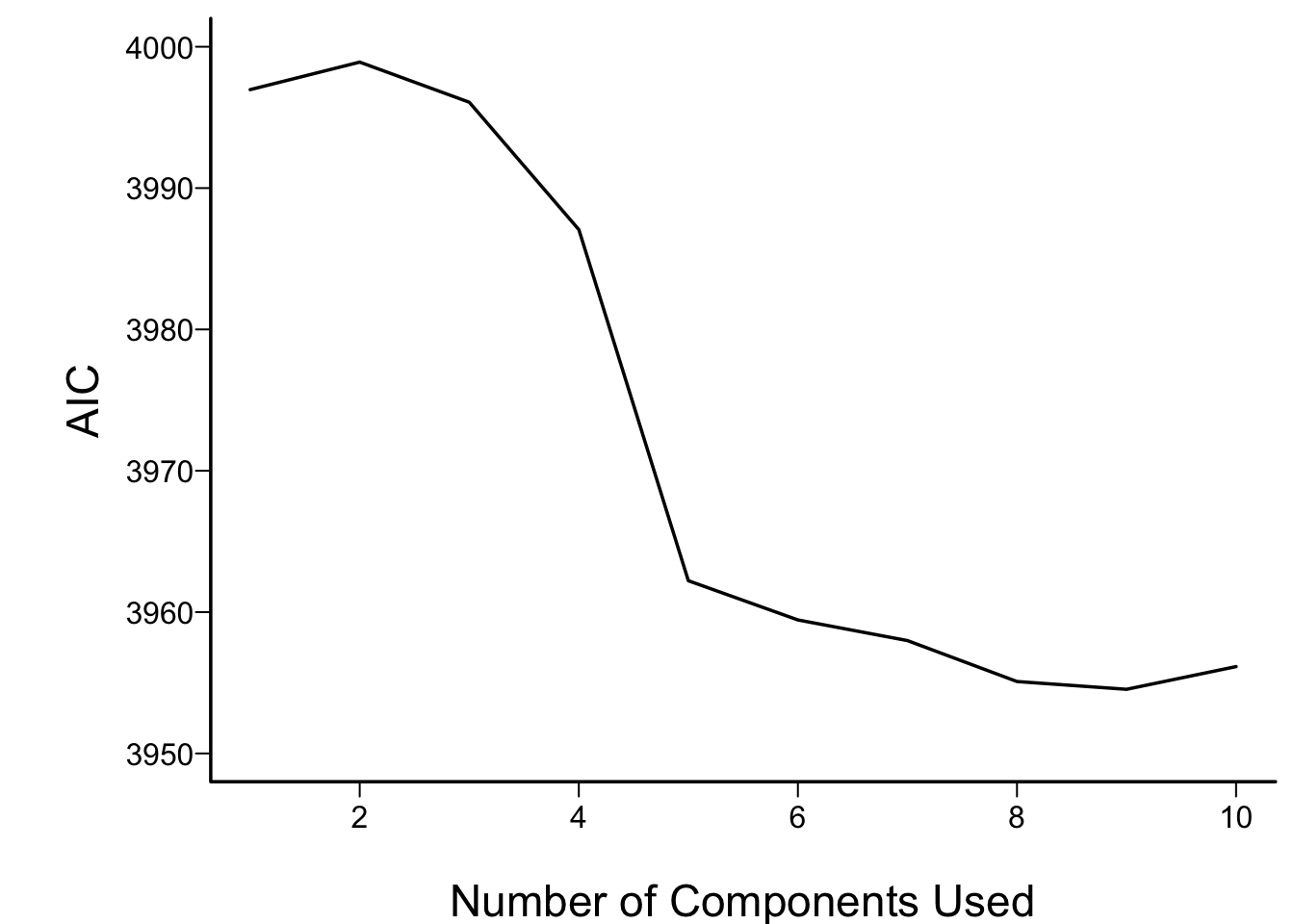

In what follows we vary the number of components used in

the Cox models from 1 to all 16, computing the AIC for each

model. AIC is related to model log likelihood penalized

for number of parameters estimated, and lower is better.

For reference, the AIC of the model using all of the original

predictors, and the AIC of a full additive spline model are shown as

horizontal lines.

```{r aic,cap='AIC of Cox models fitted with progressively more principal components. The solid blue line depicts the AIC of the model with all original covariates. The dotted blue line is positioned at the AIC of the full spline model.',scap='AIC vs. number of principal components'}

#| label: fig-impred-aic

require(rms)

spar(bty='l')

S <- with(prostate, Surv(dtime, status != "alive"))

# two-column response var.

pcs <- prin.raw$scores # pick off all PCs

aic <- numeric(16)

for(i in 1:16) {

ps <- pcs[,1:i]

aic[i] <- AIC(cph(S ~ ps))

}

plot(1:16, aic, xlab='Number of Components Used',

ylab='AIC', type='l', ylim=c(3950,4000))

f <- cph(S ~ sz + sg + log(ap) + sbp + dbp + age + wt + hg +

ekg + pf + bm + hx, data=imputed)

abline(h=AIC(f), col='blue')

## The following model in the 2nd edition no longer converges

# f <- cph(S ~ rcs(sz,5) + rcs(sg,5) + rcs(log(ap),5) +

# rcs(sbp,5) + rcs(dbp,5) + rcs(age,3) + rcs(wt,5) +

# rcs(hg,5) + ekg + pf + bm + hx,

# tol=1e-14, data=imputed)

f <- cph(S ~ rcs(sz,4) + rcs(sg,4) + rcs(log(ap),5) +

rcs(sbp,4) + rcs(dbp,4) + rcs(age,3) + rcs(wt,4) +

rcs(hg,4) + ekg + pf + bm + hx,

tol=1e-14, data=imputed)

abline(h=AIC(f), col='blue', lty=2)

```

For the money, the first 5 components adequately summarizes all variables,

if linearly transformed, and the full linear model is no better than

this. The model allowing all continuous predictors to be nonlinear is

not worth its added degrees of freedom.

<!-- TODO The model allowing all continuous predictors to be nonlinear is--->

<!-- better than the linear full model but not b etter than the 5--->

<!-- component model.--->

Next check the performance of a model derived from cluster scores of

transformed variables.

```{r}

# Compute PC1 on a subset of transcan-transformed predictors

pco <- function(v) {

f <- princmp(ptrans$transformed[,v])

print(f)

vars <- attr(f, 'results')$vars

cat('Fraction of variance explained by PC1:',

round(vars[1] / sum(vars),2), '\n')

f$scores[,1]

}

tumor <- pco(c('sz','sg','ap','bm'))

bp <- pco(c('sbp','dbp'))

cardiac <- pco(c('hx','ekg'))

# Get transformed individual variables that are not clustered

other <- ptrans$transformed[,c('hg','age','pf','wt')]

f <- cph(S ~ tumor + bp + cardiac + other) # other is matrix

AIC(f)

```

```{r}

print(f, long=FALSE, title='')

```

The `tumor` and `cardiac` clusters seem to dominate prediction

of mortality, and the AIC of the model built from cluster scores of

transformed variables compares favorably with other models

(@fig-impred-aic).

### Sparse Principal Components {#sec-impred-sparsepc}

A disadvantage of principal components is that every predictor

receives a nonzero weight for every component, so many coefficients

are involved even through the effective degrees of freedom with

respect to the response model are reduced. _Sparse principal components_ [@wit08tes] uses a penalty function to reduce the

magnitude of the loadings variables receive in the components. If an

L1 penalty is used (as with the

_lasso_, some loadings

are shrunk to zero, resulting in some simplicity. Sparse principal

components combines some elements of variable clustering, scoring of

variables within clusters, and

redundancy analysis.

@pcaPP have written a nice `R` package `pcaPP` for doing sparse PC

analysis.^[The `spcr` package is another sparse PC package that should also be considered.]

The following example uses the prostate data again.

To allow for nonlinear transformations and to score the `ekg`

variable in the prostate dataset down to a scalar, we use the

`transcan`-transformed predictors as inputs.

<!-- N% changed s$loadings to unclass() below--->

```{r spca,cap='Variance explained by individual sparse principal components (lines) along with cumulative proportion of variance explained (text)',scap='Sparse principal components'}

#| label: fig-impred-spca

s <- princmp(ptrans$transformed, k=10, method='sparse', sw=TRUE, nvmax=3)

s

plot(s)

```

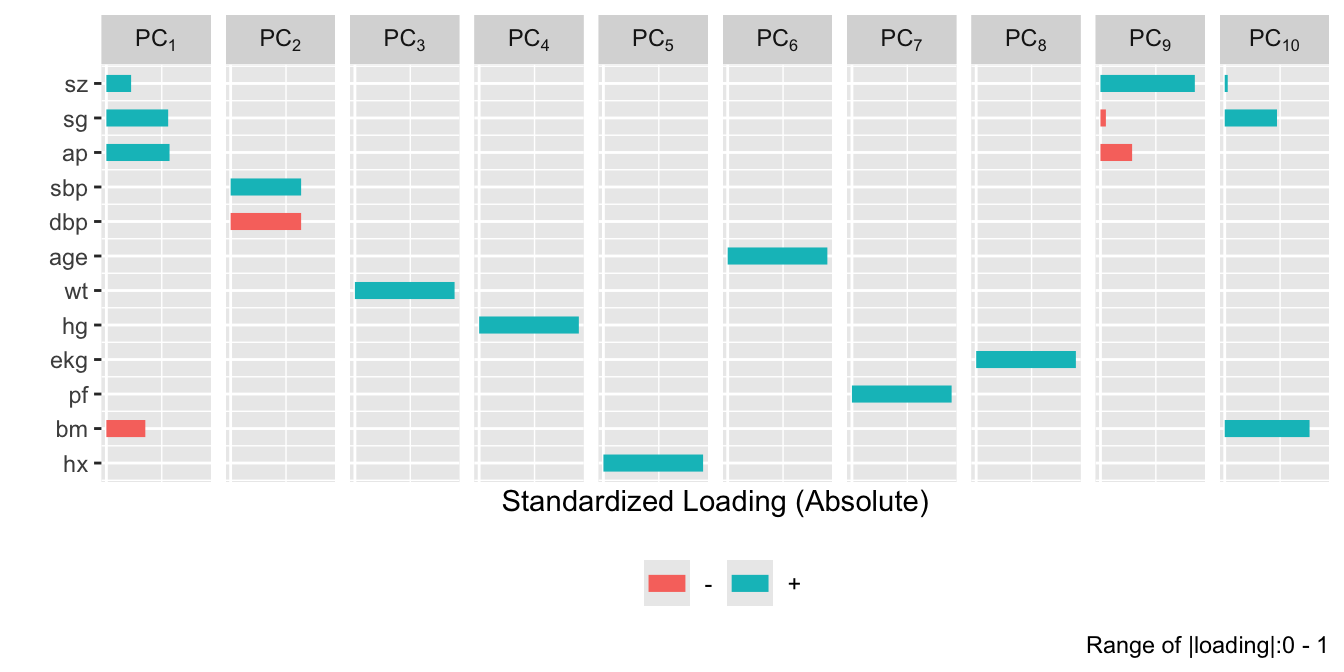

```{r}

#| fig-height: 3.5

plot(s, 'loadings', nrow=1)

```

<!-- # Computing loadings on the original transcan scales--->

<!-- xtrans <- ptrans$transformed--->

<!-- cof <- matrix(NA, nrow=ncol(xtrans), ncol=10,--->

<!-- dimnames=list(colnames(xtrans), colnames(s$scores)))--->

<!-- for(i in 1:10) cof[,i] <- coef(lsfit(xtrans, s$scores[,i]))[-1]--->

<!-- tcof <- format(round(cof, 5))--->

<!-- tcof[abs(cof) < 1e-8] <- ''--->

<!-- print(tcof, quote=FALSE)--->

Only nonzero loadings are shown. The first sparse PC is the

`tumor` cluster used above, and the second is the blood pressure

cluster. Let us see how well incomplete sparse principal component

regression predicts time until death.

```{r spc,cap='Performance of sparse principal components in Cox models',scap='Performance of sparse principal components'}

#| label: fig-impred-spc

spar(bty='l')

pcs <- s$scores # pick off sparse PCs

aic <- numeric(10)

for(i in 1:10) {

ps <- pcs[,1:i]

aic[i] <- AIC(cph(S ~ ps))

}

plot(1:10, aic, xlab='Number of Components Used',

ylab='AIC', type='l', ylim=c(3950,4000))

```

More components are required to optimize AIC than were seen in

@fig-impred-aic, but a model built from 6--8 sparse PCs

performed as well as the other models.

## Transformation Using Nonparametric Smoothers

The ACE nonparametric additive regression method of @bre85est transforms both the left-hand-side variable

and all the right-hand-side variables so as to optimize $R^{2}$. ACE

can be used to transform the predictors using

the `R` `ace` function in the `acepack`

package, called by the `transace` function in the

`Hmisc` package. `transace` does

not impute data but merely does casewise deletion of missing values.

Here `transace` is run after single imputation by `transcan`.

`binary` is used to tell `transace` which variables not to try

to predict (because they need no transformation). Several predictors

are restricted to be monotonically transformed.

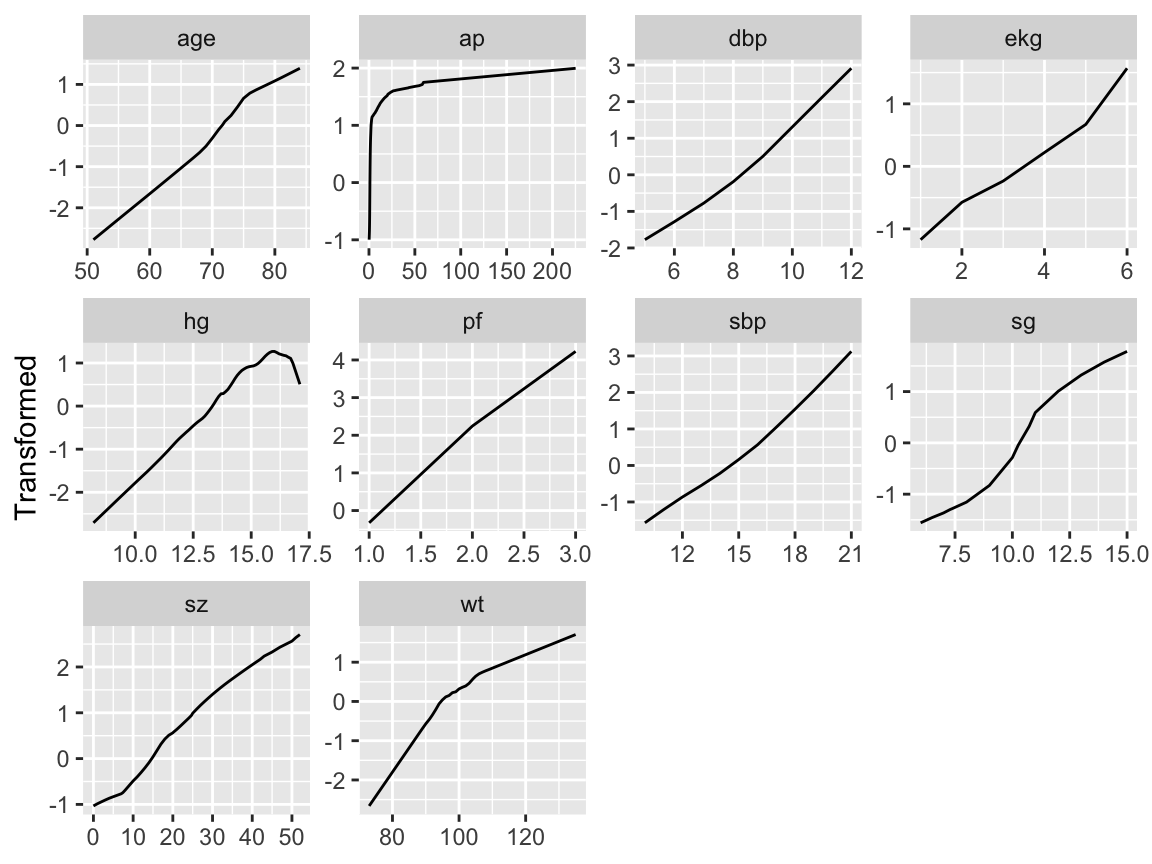

```{r ace,h=4.5,w=6,cap='Simultaneous transformation of all variables using ACE.',scap='Transformation of variables using ACE'}

#| label: fig-impred-ace

f <- transace(~ monotone(sz) + monotone(sg) + monotone(ap) + monotone(sbp) +

monotone(dbp) + monotone(age) + monotone(pf) + wt + hg +

ekg + bm + hx, data=imputed)

f

ggplot(f)

```

Except for `ekg`, `age`, and for arbitrary sign reversals, the

transformations in @fig-impred-ace determined using

`transace` were similar to those in @fig-impred-transcan.

The `transcan` transformation for `ekg` makes more sense.

## Study Questions

**Section 8.2**

1. Critique the choice of the number of parameters devoted to each

predictor.

**Section 8.3**

1. Explain why the final amount of redundancy can change from the

initial assessment.

**Section 8.5**

1. What is the meaning of the first canonical variate?

1. Explain the first row of numbers in the matrix of coefficients of

canonical variates.

1. The transformations in Figure 8.3 are not optimal for predicting

the outcome. What good can be said of them?

**Section 8.6**

1. Why in general terms do principal components work well in

predictive modeling?

1. What is the advantage of sparse PCs over regular PCs?

```{r echo=FALSE}

saveCap('08')

```