```{r include=FALSE}

require(Hmisc)

options(qproject='rms', prType='html')

require(qreport)

getRs('qbookfun.r')

hookaddcap()

knitr::set_alias(w = 'fig.width', h = 'fig.height', cap = 'fig.cap', scap ='fig.scap')

```

# Ordinal Logistic Regression {#sec-ordinal}

**Resources**: [fharrell.com/post/rpo](https://fharrell.com/post/rpo)

## Background

`r mrg(sound("olr-1"))`

* Levels of $Y$ are ordered; no spacing assumed `r ipacue()`

* If no model assumed, one can still assess association between

$X$ and $Y$

* Example: $Y=0,1,2$ corresponds to no event, heart attack,

death. Test of association between race (3 levels) and outcome (3

levels) can be obtained from a $2 \times 2$ d.f. $\chi^2$ test for

a contingency table

* If willing to assuming an ordering of $Y$ _and_ a model,

can test for association using $2 \times 1$ d.f.

* Proportional odds model: generalization of

Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney-Kruskal-Wallis-Spearman

* Can have $n$ categories for $n$ observations!

* Continuation ratio model: discrete proportional hazards model

* Ordinal models are _semiparametric_, i.e., distribution-free on the left-hand-side and parametric on the right hand $X\beta$ side of the model

## Ordinality Assumption {#sec-ordinal-ordinality}

A backwards way to look at ordinality ---

* Assume $X$ is linearly related to some appropriate log odds `r ipacue()`

* Estimate mean $X | Y$ with and without assuming the model holds

* For simplicity assume $X$ discrete

* Let $P_{jx} = \Pr(Y=j | X=x, model)$

\begin{array}{ccc}

\Pr(X=x | Y=j) &=& \Pr(Y=j | X=x) \frac{\Pr(X=x)}{\Pr(Y=j)} \nonumber \\

E(X | Y=j) &=& \sum_{x} x P_{jx} \frac{\Pr(X=x)}{\Pr(Y=j)} ,

\end{array}

and the expectation can be estimated by

$$

\hat{E}(X | Y=j) = \sum_{x} x \hat{P}_{jx} f_{x} / g_{j},

$$

where $\hat{P}_{jx}$ = estimate of $P_{jx}$ from the 1-predictor model

$$

\hat{E}(X | Y=j) = \sum_{i=1}^{n} x_{i} \hat{P}_{jx_{i}} / g_{j} .

$$

## Proportional Odds Model

`r mrg(sound("olr-2"))`

### Model

* @wal67est --- most popular ordinal response `r ipacue()`

model

* For convenience $Y=0, 1, 2, \ldots, k$

$$

\Pr[Y \geq j | X] = \frac{1}{1 + \exp[-(\alpha_{j} + X\beta)]} = \text{expit}(\alpha_{j} + X\beta)

$$

where $j=1, 2, \ldots, k$.

* $\alpha_j$ is the logit of Prob$[Y \geq j]$ when all $X$s are zero

* Odds $Y \geq j | X = \exp(\alpha_{j}+X\beta)$

* Odds $Y \geq j | X_{m}=a+1$ / Odds $Y \geq j | X_{m}=a = e^{\beta_{m}}$

* Same odds ratio $e^{\beta_{m}}$ for any $j=1,2,\ldots,k$

* Odds$[Y \geq j | X]$ / Odds$[Y \geq v | X] =

\frac{e^{\alpha_{j}+X\beta}}{e^{\alpha_{v}+X\beta}} =

e^{\alpha_{j}-\alpha_{v}}$

* Odds $Y \geq j | X$ = constant $\times$ Odds $Y \geq v | X$

* Assumes OR for 1 unit increase in age is the same when

considering the probability of death as when considering the

probability of death or heart attack

* PO model only uses ranks of $Y$; same $\hat{\beta}$s if

transform $Y$; is robust to outliers

## Assumptions and Interpretation of Parameters

### Estimation

### Residuals

* Construct binary events $Y\geq j, j=1,2,\ldots,k$ and use `r ipacue()`

corresponding predicted probabilities

$$

\hat{P}_{ij} = \text{expit}(\hat{\alpha}_{j}+X_{i}\hat{\beta}),

$$

* Score residual for subject $i$ predictor $m$:

$$

U_{im} = X_{im} ( [Y_{i}\geq j] - \hat{P}_{ij} ),

$$

* For each column of $U$ plot mean $\bar{U}_{\cdot m}$ and C.L.\

against $Y$

* Score residuals are not as useful in general semiparametric models for continuous $Y$ as they are in the Cox proportional hazards model

* Partial residuals may be more useful as they can also estimate

covariable transformations[@lan84gra; @col02mod]:

$$

r_{im} = \hat{\beta}_{m}X_{im} + \frac{Y_{i} - \hat{P}_{i}}{\hat{P}_{i}

(1 - \hat{P_{i}})},

$$

where

$$

\hat{P_{i}} = \frac{1}{1 + \exp[-(\alpha + X_{i}\hat{\beta})]} = \text{expit}(\alpha + X_{i}\hat{\beta}).

$$

* Smooth $r_{im}$ vs. $X_{im}$ to estimate how $X_{m}$ relates to

the log relative odds that $Y=1 | X_{m}$

* For ordinal $Y$ compute binary model partial res. for all

cutoffs $j$:

$$

r_{im} = \hat{\beta}_{m}X_{im} + \frac{ [Y_{i} \geq j] - \hat{P}_{ij}}{\hat{P}_{ij}

(1 - \hat{P}_{ij})},

$$

@li12new have a residual for ordinal models that

serves for the entire range of $Y$ without the need to consider

cutoffs. Their residual is useful for checking functional form of

predictors but not the proportional odds assumption.

### Assessment of Model Fit

`r ipacue()`

* @sec-ordinal-ordinality

* Stratified proportions $Y \geq j, j = 1, 2, \ldots, k$, since

$\text{logit}(Y \geq j | X) - \text{logit}(Y \geq i | X) = \alpha_{j} - \alpha_{i}$, for any constant $X$

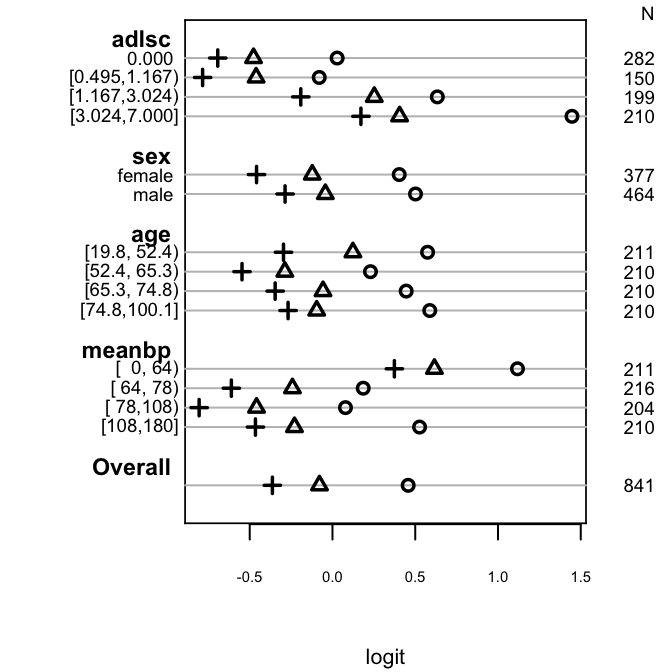

```{r po-assumpts-support,h=3.5,w=3.5,cap='Checking PO assumption separately for a series of predictors. The circle, triangle, and plus sign correspond to $Y \\geq 1, 2, 3$, respectively. PO is checked by examining the vertical constancy of distances between any two of these three symbols. Response variable is the severe functional disability scale `sfdm2` from the $1000$-patient SUPPORT dataset, with the last two categories combined because of low frequency of coma/intubation.',scap='Simple method for checking PO assumption using stratification'}

#| label: fig-ordinal-po-assumpts-support

spar(ps=7)

require(Hmisc)

getHdata(support)

sfdm <- as.integer(support$sfdm2) - 1

sf <- function(y)

c('Y>=1'=qlogis(mean(y >= 1)), 'Y>=2'=qlogis(mean(y >= 2)),

'Y>=3'=qlogis(mean(y >= 3)))

s <- summary(sfdm ~ adlsc + sex + age + meanbp, fun=sf, data=support)

plot(s, which=1:3, pch=1:3, xlab='logit', vnames='names', main='',

width.factor=1.5)

```

<!-- %NEW 2022-03-01--->

Note that computing ORs for various cutoffs and seeing disagreements among them can cause reviewers to confuse lack of fit with sampling variation (random chance). For a 4-level Y having a given vector of probabilities in a control group, let's assume PO with a true OR of 3 and simulate 10 experiments to show variation of observed ORs over all cutoffs of Y. First do it for a sample size of n=10,000 then for n=200.

```{r randomor}

p <- c(.1, .2, .3, .4)

set.seed(7)

simPOcuts(10000, odds.ratio=3, p=p)

simPOcuts( 200, odds.ratio=3, p=p)

```

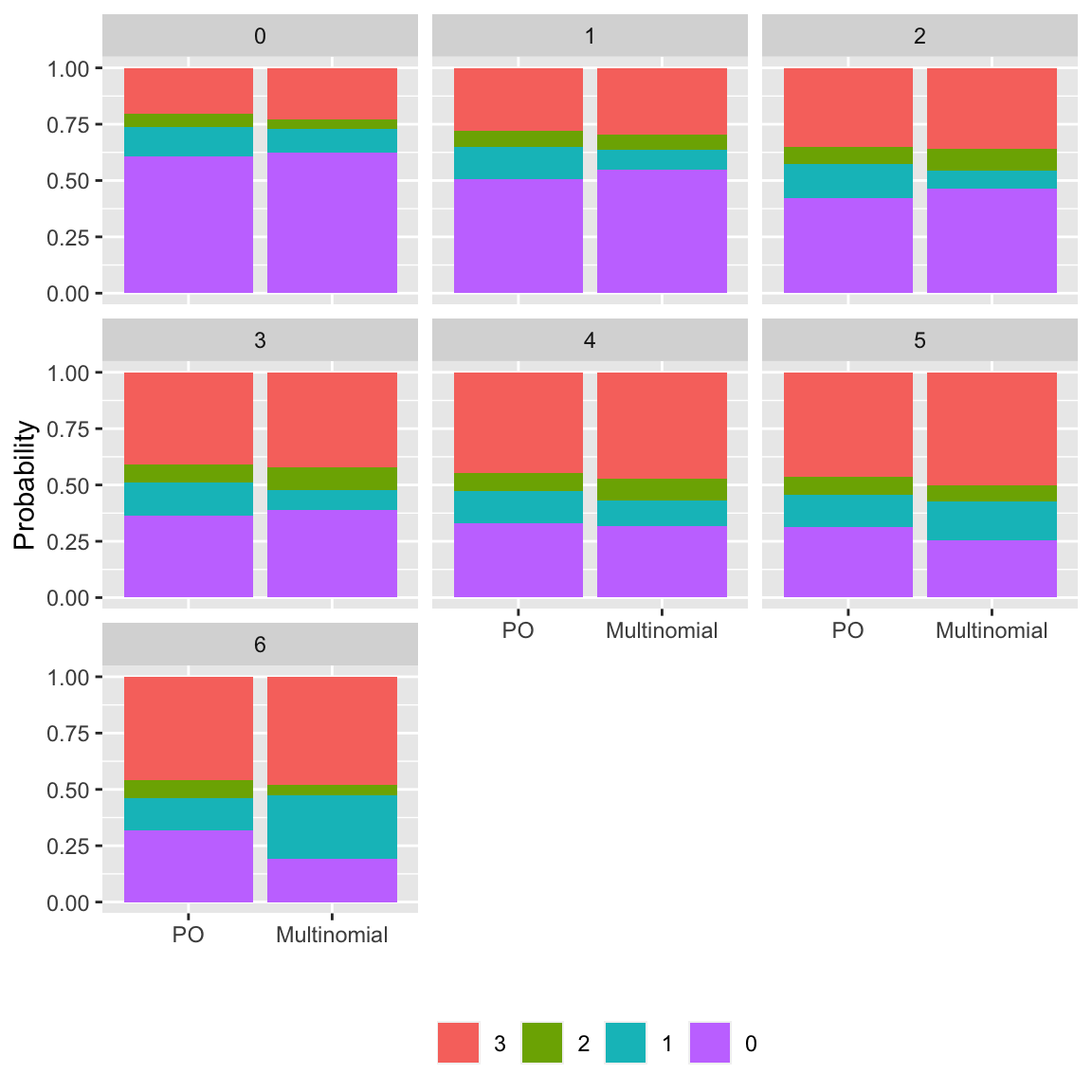

A better approach for discrete Y is to show the

_impact_ of making the PO assumption:

* Select a set of covariate settings over which to evaluate `r ipacue()`

accuracy of predictions

* Vary at least one of the predictors, i.e., the one for which you

want to assess the impact of the PO assumption

* Fit a PO model the usual way

* Fit other models that relax the PO assumption

+ to relax the PO assumption for all predictors fit a

multinomial logistic model

+ to relax the PO assumption for a subset of predictors fit a

partial PO model [@pet90par] (here using the `R` `VGAM` function)

* For all the covariate combinations evaluate predicted

probabilities for all levels of Y using the PO model and the relaxed

assumption models

* Use the bootstrap to compute confidence intervals for the

difference in predicted probabilities between a PO and a relaxed

model. This guards against over-emphasis of differences when the

sample size does not support estimation, especially for the relaxed

model with more parameters. Note that the sample problem occurs

when comparing predicted unadjusted probabilities to observed

proportions, as observed proportions can be noisy.

Example: re-do the assessment above. Note that the `VGAM` package `vglm` function did not converge when fitting the partial proportional odds model. So in what follows we only compare the fully PO model with the fully non-PO multinomial model.

```{r po-assumpts-impact,h=6,w=6,cap='Checking the impact of the PO assumption by comparing predicted probabilities of all outcome categories from a PO model with a multinomial logistic model that assumes PO for no variables',scap='Checking impact of the PO assumption'}

#| label: fig-ordinal-po-assumpts-impact

spar(ps=7)

require(rms)

require(ggplot2)

# One headache: since using a non-rms fitting function need to hard

# code knots in splines. This is not necessary in rms 6.5-0 and later

kq <- seq(0.05, 0.95, length=4)

kage <- quantile(support$age, kq, na.rm=TRUE)

kbp <- quantile(support$meanbp, kq, na.rm=TRUE)

d <- expand.grid(adlsc=0:6, sex='male', age=65, meanbp=78)

# Because of very low frequency (7) of sfdm=3, combine categories 3, 4

support$sfdm3 <- pmin(sfdm, 3)

done.impact <- TRUE

if(done.impact) w <- readRDS('impactPO.rds') else {

set.seed(1)

w <- impactPO(sfdm3 ~ pol(adlsc, 2) + sex + rcs(age, kage) +

rcs(meanbp, kbp),

newdata=d, B=300, data=support)

saveRDS(w, 'impactPO.rds')

}

w

# Reverse levels of y so stacked bars have higher y located higher

revo <- function(z) {

z <- as.factor(z)

factor(z, levels=rev(levels(as.factor(z))))

}

ggplot(w$estimates, aes(x=method, y=Probability, fill=revo(y))) +

facet_wrap(~ adlsc) + geom_col() +

xlab('') + guides(fill=guide_legend(title='')) +

theme(legend.position='bottom')

```

AIC indicates that a model assuming PO nowhere is better than

one that assumes PO everywhere. In an earlier run in which convergence was obtained using `vglm`, the PPO model with far fewer

parameters is just as good, and is also better than the PO model,

indicating non-PO with respect to `adlsc`.

The fit of the PO model is such that cell probabilities become more

inaccurate for higher level outcomes. This can also be seen by the

increasing mean absolute differences with probability estimates from

the PO model. Bootstrap nonparametric percentile confidence intervals

(300 resamples, not all of which converged)

for differences in predicted cell probabilities between the PO model

and a relaxed model are also found above. Some of these intervals

exclude 0, in line with the other evidence for non-PO.

See

[fharrell.com/post/impactpo](https://fharrell.com/post/impactpo)

for a similar example.

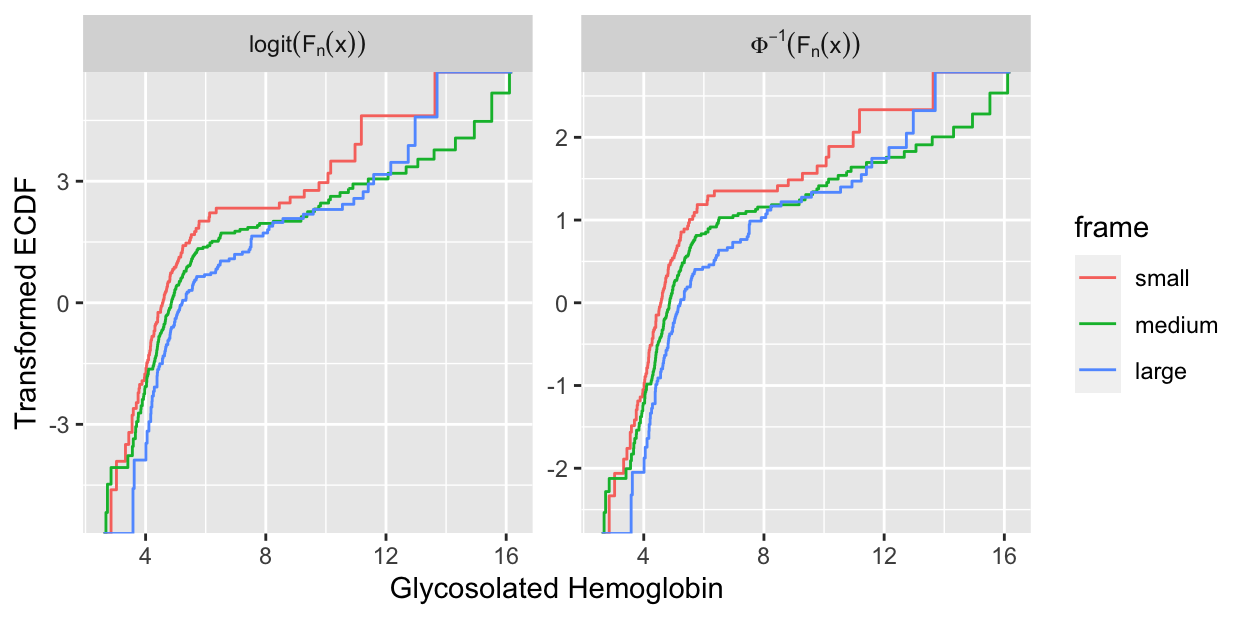

When $Y$ is continuous or almost continuous and $X$ is discrete, the

PO model assumes that the logit of the cumulative distribution

function of $Y$ is parallel across categories of $X$.

The corresponding, more rigid, assumptions of the ordinary linear

model (here, parametric ANOVA) are parallelism and linearity of the

normal inverse cumulative

distribution function across categories of $X$. As an example

consider the web site's `diabetes` dataset, where we consider the

distribution of log glycohemoglobin across subjects' body frames.

```{r glyhb,h=3.25,w=6.5,cap='Transformed empirical cumulative distribution functions stratified by body frame in the `diabetes` dataset. Left panel: checking all assumptions of the parametric ANOVA. Right panel: checking all assumptions of the PO model (here, Kruskal--Wallis test).',scap='Checking assumptions of PO and parametric model'}

#| label: fig-ordinal-glyhb

require(data.table)

getHdata(diabetes)

d <- subset(diabetes, ! is.na(frame))

setDT(d) # make it a data table

w <- d[, ecdfSteps(glyhb, extend=c(2.6, 16.2)), by=frame]

# ecdfSteps is in Hmisc

# Duplicate ECDF points for trying 2 transformations

u <- rbind(data.table(trans='paste(Phi^-1, (F[n](x)))', w[, z := qnorm(y) ]),

data.table(trans='logit(F[n](x))', w[, z := qlogis(y)]))

# See https://hbiostat.org/rflow/graphics.html#sec-graphics-ggplot2

ggplot(u, aes(x, z, color=frame)) + geom_step() +

facet_wrap(~ trans, label='label_parsed', scale='free_y') +

ylab('Transformed ECDF') +

xlab(hlab(glyhb)) # hlab is in Hmisc; looks up label in d

```

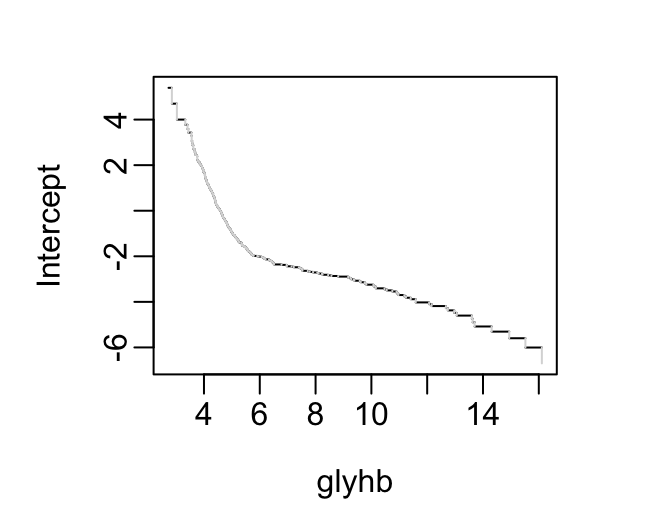

See how these distributions are reflected in proportional odds model intercepts.

```{r ints}

#| fig-height: 2.75

#| fig-width: 3.5

f <- orm(glyhb ~ frame, data=d)

plotIntercepts(f)

```

<!-- NEW -->

Especially for continuous predictors, the `rms` package `ordParallel` provides graphical and formal assessments of proportionality (adequacy of link). See @sec-cony for an example.

### Quantifying Predictive Ability

### Describing the Model

For PO models there are four and sometimes five types of

relevant predictions:

1. logit$[Y \geq j | X]$, i.e., the linear predictor `r ipacue()`

1. Prob$[Y \geq j | X]$

1. Prob$[Y = j | X]$

1. Quantiles of $Y | X$ (e.g., the median^[If $Y$ does not have very many levels, the median will be a discontinuous function of $X$ and may not be satisfactory.])

1. $E(Y | X)$ if $Y$ is interval scaled.

Graphics:

1. Partial effect plot (prob. scale or mean) `r ipacue()`

1. Odds ratio chart

1. Nomogram (possibly including the mean)

### Validating the Fitted Model

### `R` Functions

`r mrg(sound("olr-3"))`

The `rms` package's `lrm` and `orm` functions fit the PO model

directly, assuming that the levels of the response variable (e.g., the

`levels` of a `factor` variable) are listed in the proper

order. `predict` computes all types of estimates except for quantiles.

`orm` allows for more link functions than the logistic and is

intended to efficiently handle hundreds of intercepts as happens when

$Y$ is continuous.

The `R` functions `popower` and `posamsize` (in the

`Hmisc` package) compute power and sample size estimates for

ordinal responses using the proportional odds model.

The function `plot.xmean.ordinaly` in `rms` computes and graphs the

quantities described in @sec-ordinal-ordinality. It plots

simple $Y$-stratified means overlaid with $\hat{E}(X | Y=j)$, with

$j$ on the $x$-axis. The $\hat{E}$s are computed for both PO and

continuation ratio ordinal logistic models.

The `Hmisc` package's `summary.formula` function is also useful

for assessing the PO assumption.

Generic `rms` functions such as `validate`, `calibrate`,

and `nomogram` work with PO model fits from `lrm` as long as the

analyst specifies which intercept(s) to use.

`rms` has a special function generator `Mean` for

constructing an easy-to-use function for getting the predicted mean

$Y$ from a PO model. This is handy with `plot` and `nomogram`.

If the fit has been run through `bootcov`, it is easy to use the

`Predict` function to estimate bootstrap confidence limits for

predicted means.

## Continuation Ratio Model

`r mrg(sound("olr-4"))`

### Model

Unlike the PO model, which is based on _cumulative_ probabilities, the

continuation ratio (CR) model is based on _conditional_ probabilities.

The (forward) CR model[@fie07ana; @arm89ord; @ber91ana] is stated as follows

for $Y=0,\ldots,k$:

$$\begin{array}{c}

\Pr(Y=j | Y \geq j, X) &=& \text{expit}(\theta_{j} + X\gamma)

\nonumber \\

\text{logit}(Y=0 | Y \geq 0, X) &=& \text{logit}(Y=0 | X) \nonumber \\

&=& \theta_{0} + X\gamma \\

\text{logit}(Y=1 | Y \geq 1, X) &=& \theta_{1} + X\gamma \nonumber \\

\ldots & & \nonumber \\

\text{logit}(Y=k-1 | Y \geq k-1, X) &=& \theta_{k-1} + X\gamma . \nonumber

\end{array}$$ {#eq-cr-equation}

The CR model has been said to be likely to fit ordinal responses when

subjects have to "pass through" one category to get to the next

The CR model is a discrete version of the Cox proportional hazards

model. The discrete hazard function is defined as $\Pr(Y=j | Y \geq j)$.

Advantage of CR model: easy to allow unequal slopes across $Y$ for

selected $X$.

### Assumptions and Interpretation of Parameters

### Estimation

### Residuals

To check CR model assumptions, binary logistic model partial residuals

are again valuable. We separately fit a sequence of binary logistic

models using a series of binary events and the corresponding

applicable (increasingly small) subsets of subjects, and plot smoothed partial

residuals against $X$ for all of the binary events. Parallelism in

these plots indicates that the CR model's constant $\gamma$

assumptions are satisfied.

### Assessment of Model Fit

### Extended CR Model

### Role of Penalization in Extended CR Model

### Validating the Fitted Model

### `R` Functions

The `cr.setup` function in `rms` returns a list of vectors

useful in constructing a dataset used to trick a binary logistic

function such as `lrm` into fitting CR models.

```{r echo=FALSE}

saveCap('13')

```