```{r include=FALSE}

require(Hmisc)

options(qproject='rms', prType='html')

require(qreport)

getRs('qbookfun.r')

hookaddcap()

knitr::set_alias(w = 'fig.width', h = 'fig.height', cap = 'fig.cap', scap ='fig.scap')

```

# Binary Logistic Regression Case Study 1 {#sec-lrcase1}

**Case Study in Binary Logistic Regression, Model Selection and Approximation: Predicting Cause of Death**

## Overview

This chapter contains a case study on developing, describing, and

validating a binary logistic regression model. In addition, the

following methods are exemplified:

1. Data reduction using incomplete linear and nonlinear principal components

1. Use of AIC to choose from five modeling variations,

deciding which is best for the number of parameters

1. Model simplification using stepwise variable selection and

approximation of the full model

1. The relationship between the degree of approximation and the

degree of predictive discrimination loss

1. Bootstrap validation that includes penalization for model

uncertainty (variable selection) and that demonstrates a loss of

predictive discrimination over the full model even when compensating

for overfitting the full model.

The data reduction and pre-transformation methods used here were discussed in

more detail in @sec-impred. Single imputation will be

used because of the limited quantity of missing data.

## Background

Consider the randomized trial of estrogen for treatment of

prostate cancer [@bya80cho] described in @sec-impred. In

this trial, larger doses of estrogen reduced the effect of prostate

cancer but at the cost of increased risk of cardiovascular death.

@kay86tre did a formal analysis of the competing risks for

cancer, cardiovascular, and other deaths. It can also be quite

informative to study how treatment and baseline variables relate to

the cause of death for those patients who died. [@lar85mix] We

subset the original dataset of those patients dying from prostate

cancer ($n=130$), heart or vascular disease ($n=96$), or

cerebrovascular disease ($n=31$). Our goal is to predict

cardiovascular--cerebrovascular death (`cvd`, $n=127$) given the

patient died from

either `cvd` or prostate cancer. Of interest is whether the time

to death has an effect on the cause of death, and whether the

importance of certain variables depends on the time of death.

## Data Transformations and Single Imputation

In `R`, first obtain the desired subset of the data and do some preliminary

calculations such as combining an infrequent category with the next

category, and dichotomizing `ekg` for use in ordinary principal

components (PCs).

```{r}

require(rms)

options(prType='html')

getHdata(prostate)

prostate <-

within(prostate, {

levels(ekg)[levels(ekg) %in%

c('old MI','recent MI')] <- 'MI'

ekg.norm <- 1*(ekg %in% c('normal','benign'))

levels(ekg) <- abbreviate(levels(ekg))

pfn <- as.numeric(pf)

levels(pf) <- levels(pf)[c(1,2,3,3)]

cvd <- status %in% c("dead - heart or vascular",

"dead - cerebrovascular")

rxn = as.numeric(rx) })

# Use transcan to compute optimal pre-transformations

ptrans <- # See Figure (* @fig-prostate-transcan*)

transcan(~ sz + sg + ap + sbp + dbp +

age + wt + hg + ekg + pf + bm + hx + dtime + rx,

imputed=TRUE, transformed=TRUE,

data=prostate, pl=FALSE, pr=FALSE)

# Use transcan single imputations

imp <- impute(ptrans, data=prostate, list.out=TRUE)

NAvars <- all.vars(~ sz + sg + age + wt + ekg)

for(x in NAvars) prostate[[x]] <- imp[[x]]

subset <- prostate$status %in% c("dead - heart or vascular",

"dead - cerebrovascular","dead - prostatic ca")

trans <- ptrans$transformed[subset,]

psub <- prostate[subset,]

```

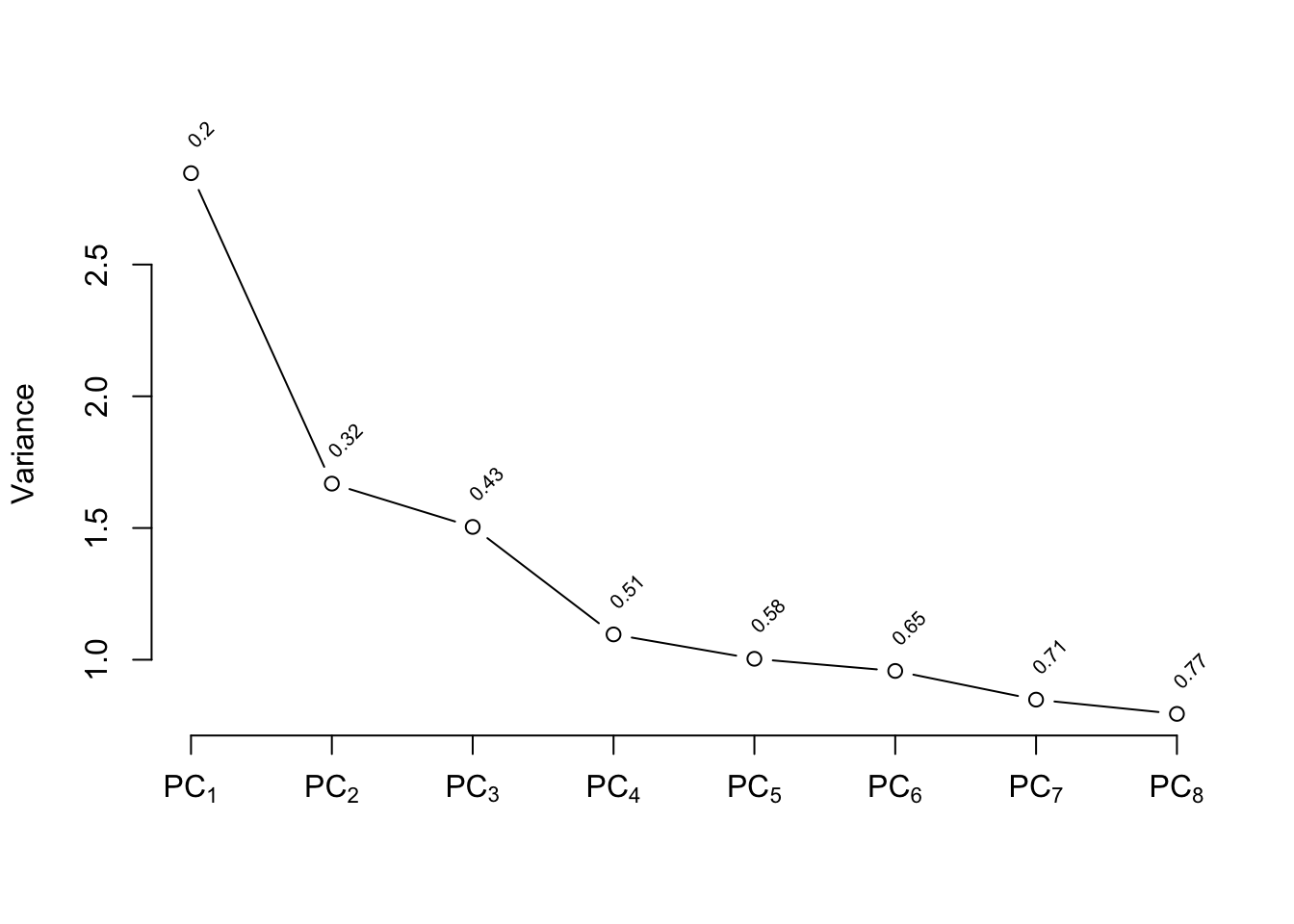

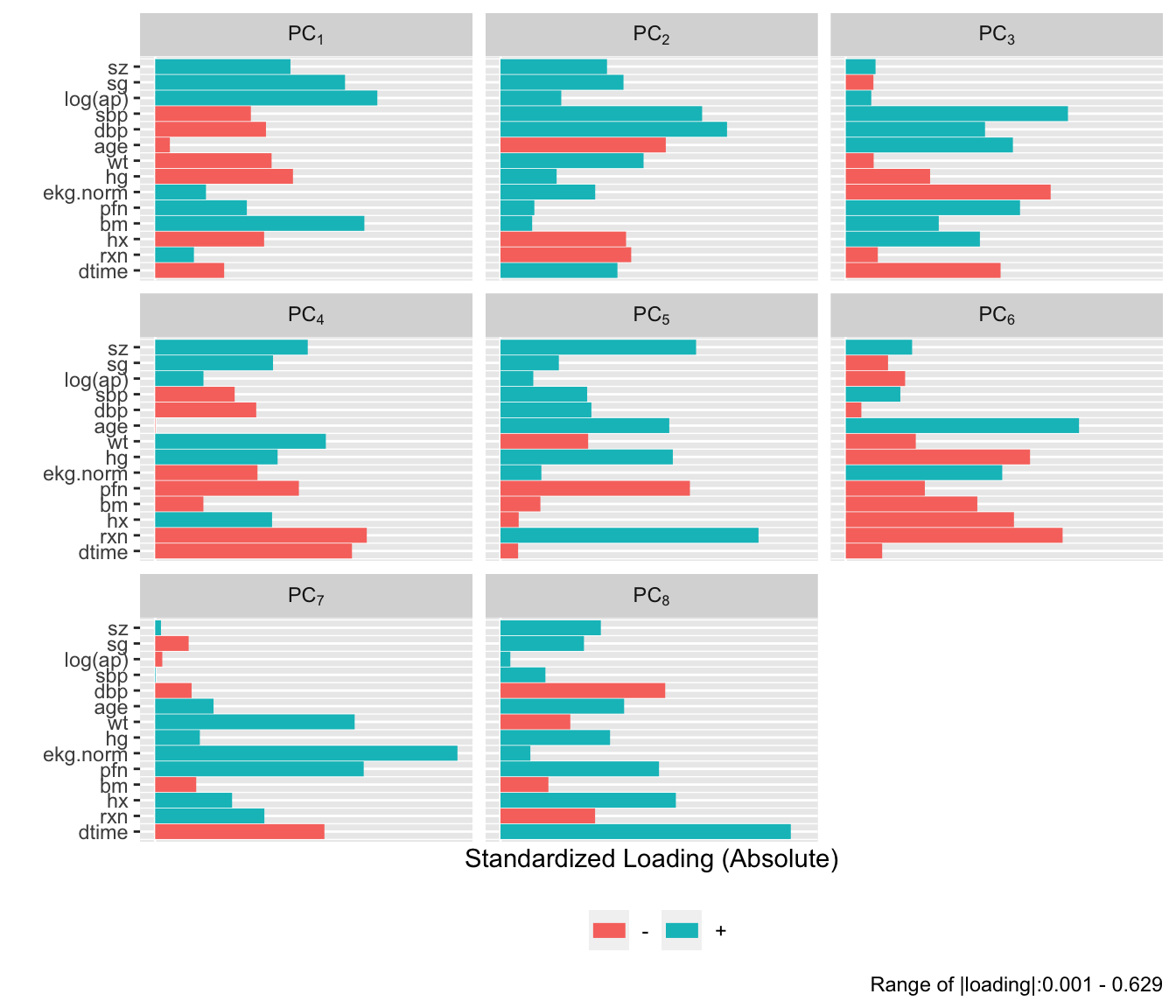

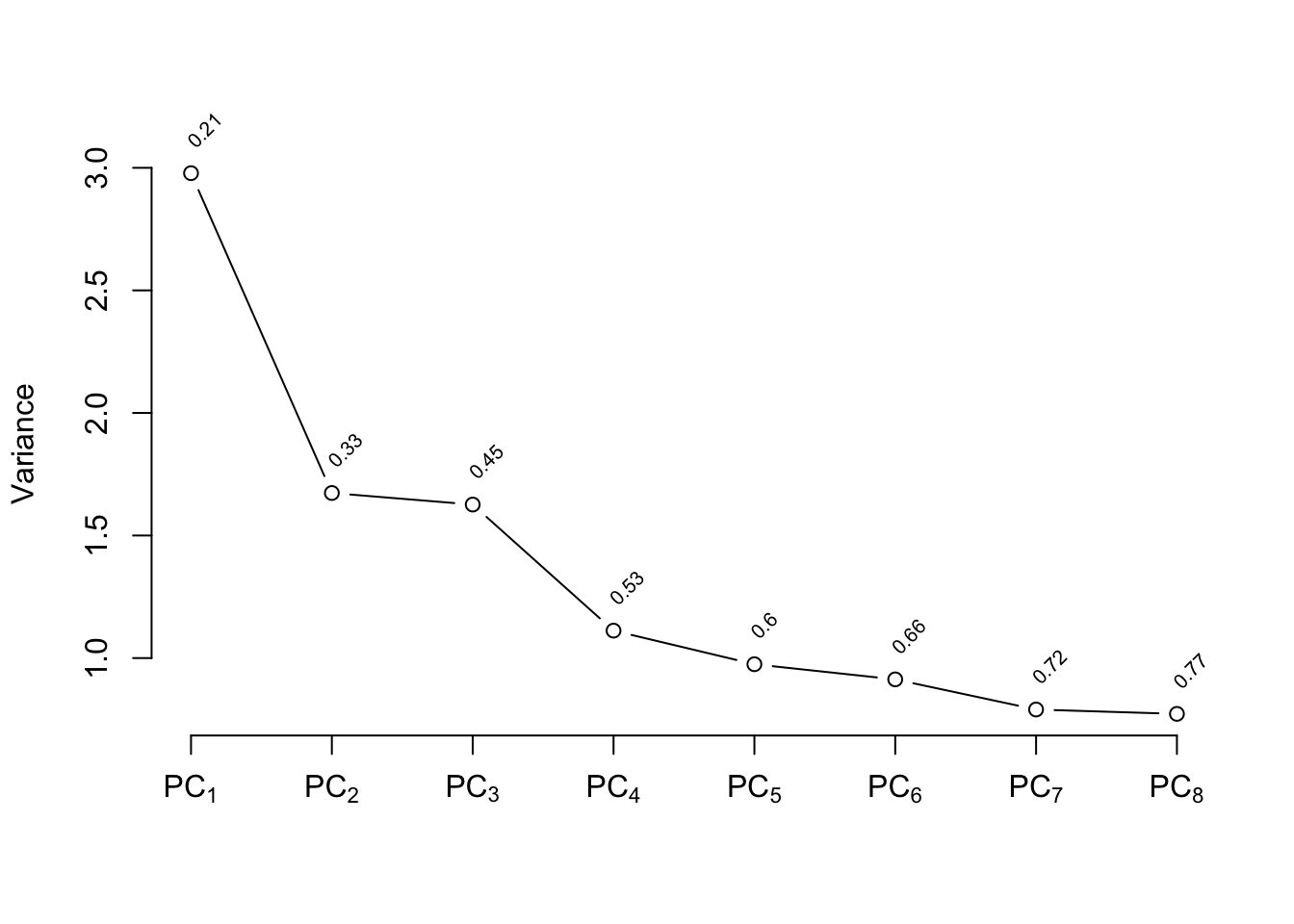

## Regression on Original Variables, Principal Components and Pretransformations {#sec-lrcase1-pc}

We first examine the performance of data reduction in predicting the

cause of death, similar to what we did for survival time in

Section @sec-impred-pc. The

first analyses assess how well PCs (on raw and

transformed variables) predict the cause of death.

There are 127 `cvd`s. We use the 15:1 rule of thumb

discussed in @sec-multivar-overfit to justify using the

first 8 PCs. `ap` is log-transformed because of

its extreme distribution. We use `Hmisc::princmp`.

```{r}

# Compute the first 8 PCs on raw variables then on

# transformed ones

p <- princmp(~ sz + sg + log(ap) + sbp + dbp + age +

wt + hg + ekg.norm + pfn + bm + hx + rxn + dtime,

data=psub, k=8, sw=TRUE, kapprox=2)

p

plot(p)

```

```{r}

#| fig-height: 6

plot(p, 'loadings')

```

```{r}

pc8 <- p$scores

f8 <- lrm(cvd ~ pc8, data=psub)

p <- princmp(trans, k=8, sw=TRUE, kapprox=2)

p

plot(p)

```

```{r}

#| fig-height: 6

plot(p, 'loadings')

```

```{r}

pc8t <- p$scores

f8t <- lrm(cvd ~ pc8t, data=psub)

# Fit binary logistic model on original variables

# x=TRUE y=TRUE are for test='LR', validate, calibrate

f <- lrm(cvd ~ sz + sg + log(ap) + sbp + dbp + age +

wt + hg + ekg + pf + bm + hx + rx + dtime,

x=TRUE, y=TRUE, data=psub)

# Expand continuous variables using splines

g <- lrm(cvd ~ rcs(sz,4) + rcs(sg,4) + rcs(log(ap),4) +

rcs(sbp,4) + rcs(dbp,4) + rcs(age,4) + rcs(wt,4) +

rcs(hg,4) + ekg + pf + bm + hx + rx + rcs(dtime,4),

data=psub)

# Fit binary logistic model on individual transformed var.

h <- lrm(cvd ~ trans, data=psub)

```

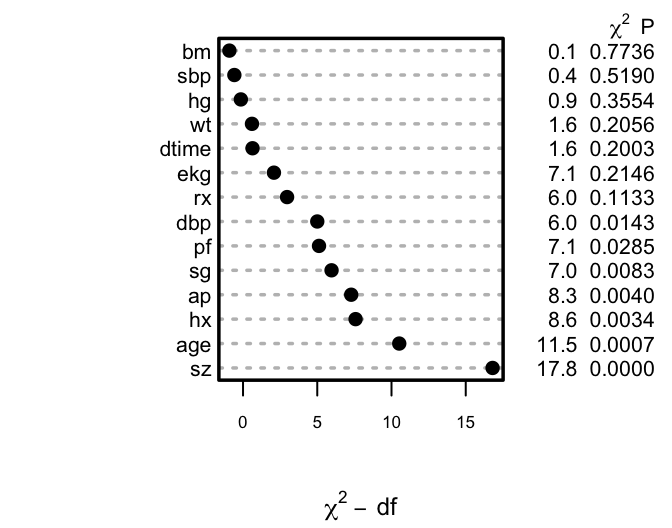

The five approaches to modeling the outcome are compared using AIC

(where smaller is better).

```{r}

c(f8=AIC(f8), f8t=AIC(f8t), f=AIC(f), g=AIC(g), h=AIC(h))

```

Based on AIC, the more traditional model fitted to the raw data and assuming

linearity for all the continuous predictors has only a slight chance of

producing worse cross-validated predictive accuracy than other methods.

The chances are also good that effect estimates from this simple

model will have competitive mean squared errors.

## Description of Fitted Model

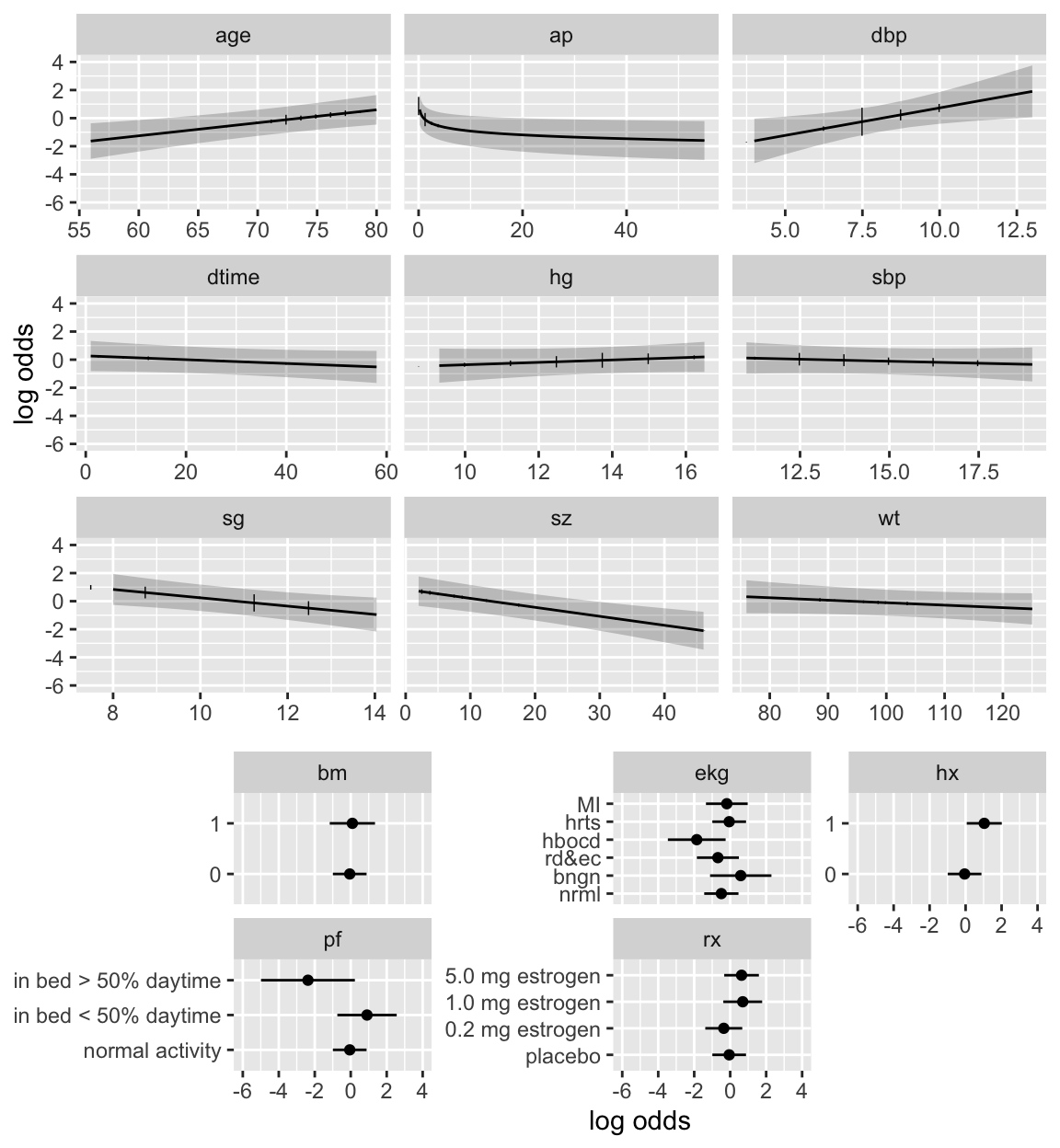

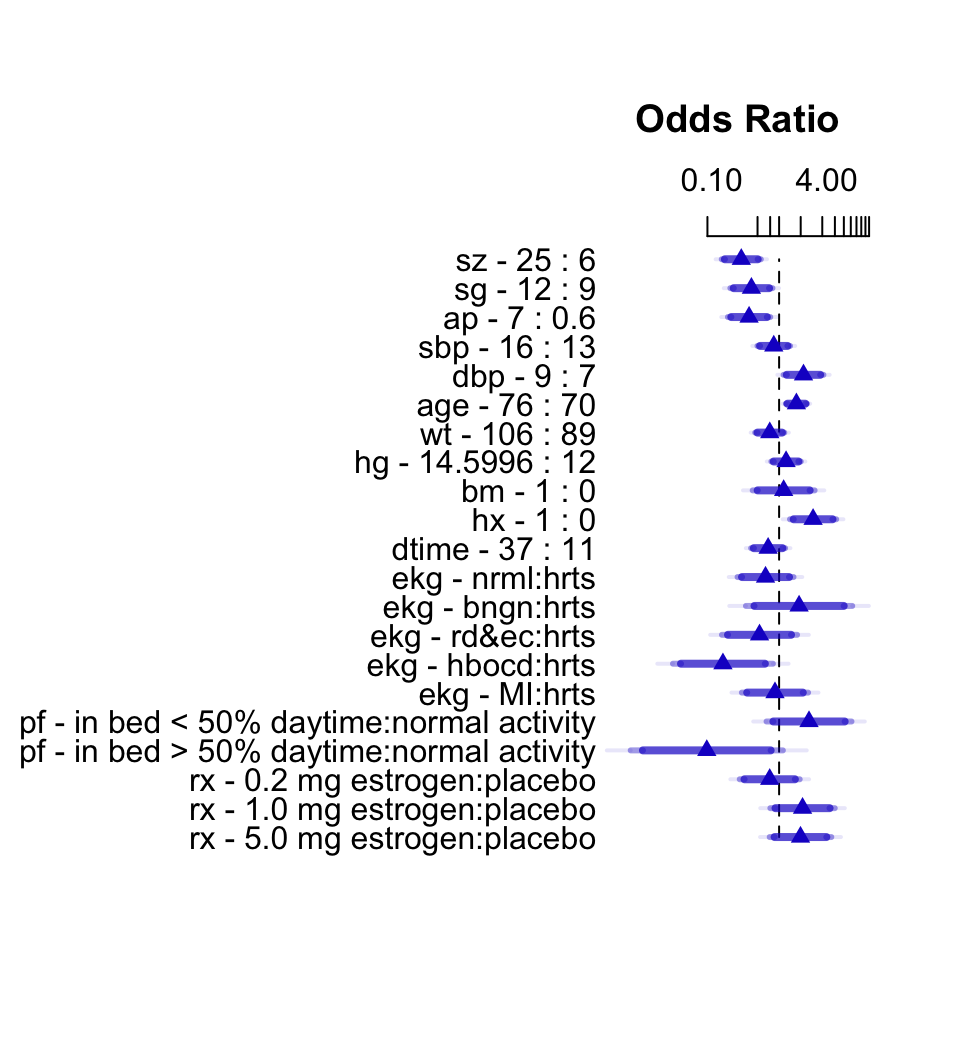

Here we describe the simple all-linear full model.

Summary statistics and Wald and likelihood ratio ANOVA tables are below, followed by partial effects plots with pointwise confidence bands, and odds ratios

over default ranges of predictors.

```{r}

f

anova(f)

an <- anova(f, test='LR')

an

```

```{r h=2.75,w=3.5,cap='Ranking of apparent importance of predictors of cause of death using LR statistics'}

#| label: fig-lrcase1-full

spar(ps=8,top=0.5)

plot(an)

s <- f$stats

gamma.hat <- (s['Model L.R.'] - s['d.f.'])/s['Model L.R.']

```

```{r h=6.5,w=6,cap='Partial effects (log odds scale) in full model for cause of death, along with vertical line segments showing the raw data distribution of predictors',scap='Partial effects in cause of death model'}

#| label: fig-lrcase1-fullpeffects

dd <- datadist(psub); options(datadist='dd')

ggplot(Predict(f), sepdiscrete='vertical', vnames='names',

rdata=psub,

histSpike.opts=list(frac=function(f) .1*f/max(f) ))

```

```{r h=5.5,w=5,top=2,cap='Interquartile-range odds ratios for continuous predictors and simple odds ratios for categorical predictors. Numbers at left are upper quartile : lower quartile or current group : reference group. The bars represent $0.9, 0.95, 0.99$ confidence limits. The intervals are drawn on the log odds ratio scale and labeled on the odds ratio scale. Ranges are on the original scale.',scap='Interquartile-range odds ratios and confidence limits'}

#| label: fig-lrcase1-fullor

plot(summary(f), log=TRUE)

```

The van Houwelingen--Le Cessie heuristic

shrinkage estimate (@eq-heuristic-shrink) is

$\hat{\gamma}=`r round(gamma.hat,2)`$, indicating that this model

will validate on new data about `r round(100*(1 - gamma.hat))`%

worse than on this dataset.

## Backwards Step-Down

Now use fast backward step-down (with total residual AIC as the stopping

rule) to identify the variables that explain the bulk of the cause of

death. Later validation will take this screening of variables into

account.

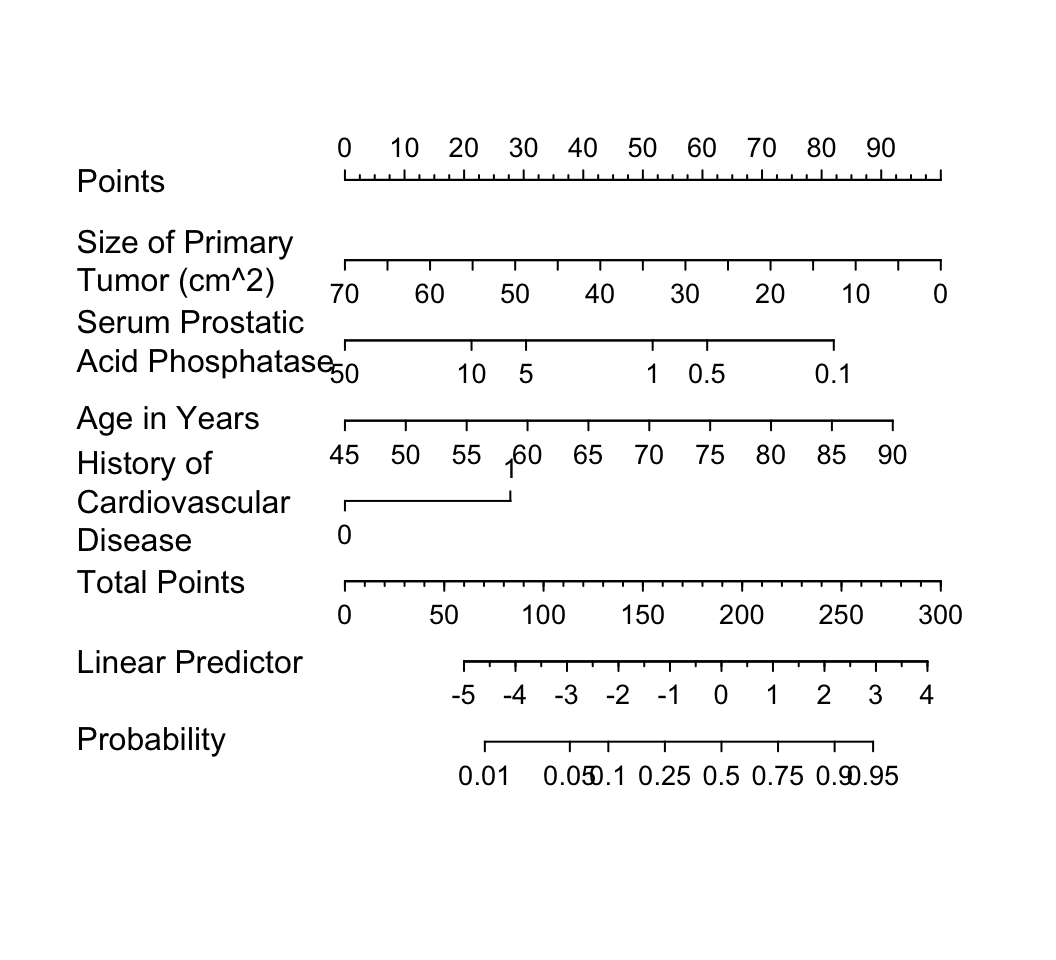

The greatly reduced model results in a simple nomogram.

```{r}

fastbw(f)

```

```{r}

fred <- lrm(cvd ~ sz + log(ap) + age + hx, data=psub)

latex(fred)

```

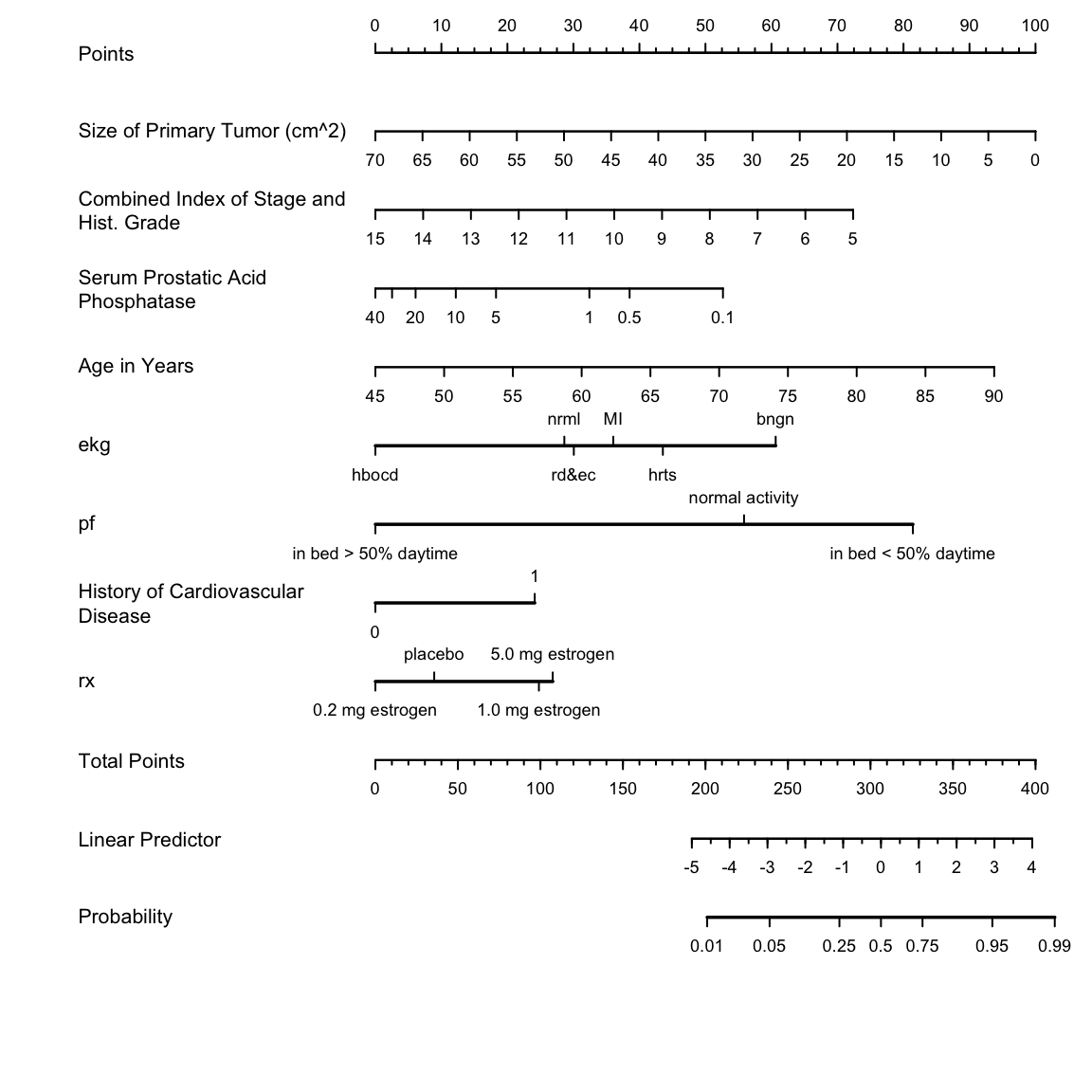

```{r w=5.5,h=5,ps=8,cap='Nomogram calculating $X\\hat{\\beta}$ and $\\hat{P}$ for `cvd` as the cause of death, using the step-down model. For each predictor, read the points assigned on the 0--100 scale and add these points. Read the result on the `Total Points` scale and then read the corresponding predictions below it.',scap='Nomogram for obtaining $X\\hat{\\beta}$ and $\\hat{P}$ from step-down model'}

#| label: fig-lrcase1-nom

nom <- nomogram(fred, ap=c(.1, .5, 1, 5, 10, 50),

fun=plogis, funlabel="Probability",

fun.at=c(.01,.05,.1,.25,.5,.75,.9,.95,.99))

plot(nom, xfrac=.45)

```

It is readily seen from this model that patients with a

history of heart disease, and patients with less extensive prostate cancer

are those more likely to die from `cvd` rather than from

cancer.

But beware that it is easy to over-interpret findings when using

unpenalized estimation, and confidence intervals are too

narrow. Let us use the bootstrap to study the uncertainty in the

selection of variables and to penalize for this uncertainty when

estimating predictive performance of the model. The variables

selected in the first 20 bootstrap resamples are shown, making it

obvious that the set of "significant" variables, i.e., the final

model, is somewhat arbitrary.

```{r results='hide'}

v <- validate(f, B=200, bw=TRUE)

```

```{r}

print(v, B=20, digits=3)

```

The slope shrinkage ($\hat{\gamma}$) is a bit lower than was estimated

above. There is drop-off in all indexes. The estimated likely future

predictive discrimination of the model as measured by Somers' $D_{xy}$

fell from `r round(v['Dxy','index.orig'],3)` to

`r round(v['Dxy','index.corrected'],3)`. The latter estimate is

the one that should be claimed when describing model performance.

A nearly unbiased estimate of future calibration of the

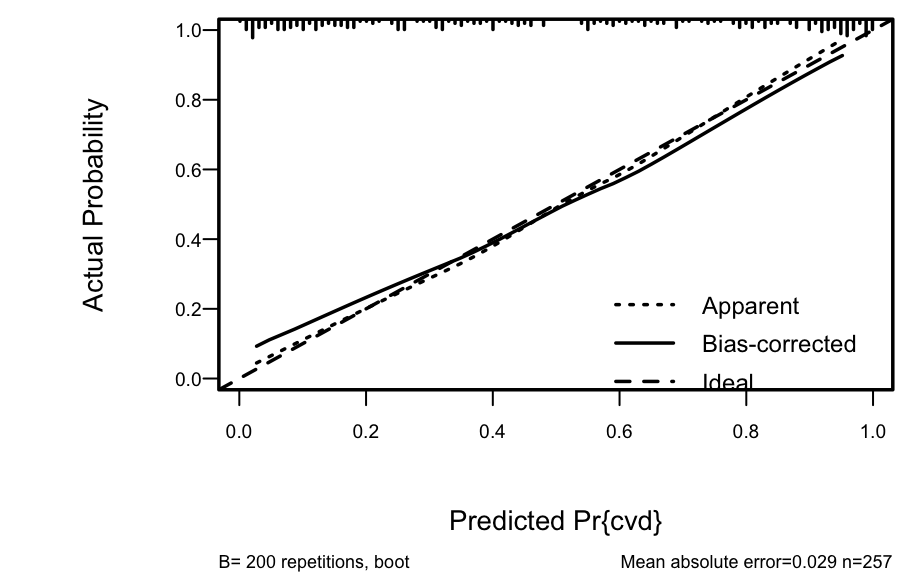

stepwise-derived model is given below.

```{r h=3,w=4.75,cap='Bootstrap overfitting-corrected calibration curve estimate for the backwards step-down cause of death logistic model, along with a rug plot showing the distribution of predicted risks. The smooth nonparametric calibration estimator (`loess`) is used.',scap='Bootstrap nonparametric calibration curve for reduced cause of death model'}

#| label: fig-lrcase1-cal

spar(ps=9, bot=1)

cal <- calibrate(f, B=200, bw=TRUE)

plot(cal)

```

The amount of overfitting seen in @fig-lrcase1-cal is

consistent with the indexes produced by the `validate` function.

For comparison, consider a bootstrap validation of the full model

without using variable selection.

```{r}

vfull <- validate(f, B=200)

print(vfull, digits=3)

```

Compared to the validation of the full model, the step-down model

has less optimism, but it started with a smaller $D_{xy}$ due to

loss of information from removing moderately important variables. The

improvement

in optimism was not enough to offset the effect of eliminating variables.

If shrinkage were used with the full model, it would have better

calibration and discrimination than the reduced model, since shrinkage

does not diminish $D_{xy}$. Thus stepwise variable selection failed

at delivering excellent predictive discrimination.

Finally, compare previous results with a bootstrap validation of a

step-down model using a better significance level for a variable to

stay in the model ($\alpha=0.5$, @ste00pro) and using individual

approximate Wald tests rather than tests combining all deleted variables.

```{r}

v5 <- validate(f, bw=TRUE, sls=0.5, type='individual', B=200)

```

```{r}

print(v5, digits=3, B=0)

```

The performance statistics are midway between the full model and the

smaller stepwise model.

## Model Approximation {#sec-lrcase1-approx}

Frequently a better approach than stepwise variable selection is to

approximate the full model, using its estimates of precision, as

discussed in @sec-val-approx. Stepwise variable

selection as well as regression trees are useful for making the

approximations, and the sacrifice in predictive accuracy is always apparent.

We begin by computing the "gold standard" linear predictor from the

full model fit ($R^{2} = 1.0$), then running backwards step-down OLS

regression to approximate it.

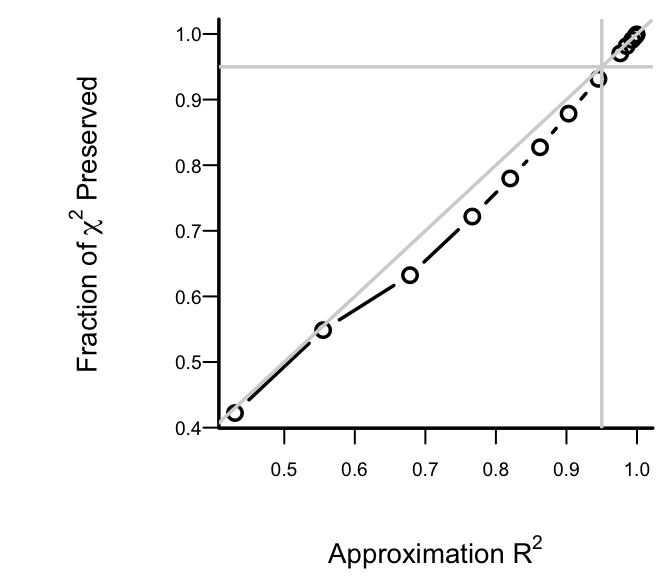

```{r h=3,w=3.5,cap='Fraction of explainable variation (full model LR $\\chi^2$) in `cvd` that was explained by approximate models, along with approximation accuracy ($x$-axis)',scap='Model approximation vs. LR $\\chi^2$ preserved'}

#| label: fig-lrcase1-approxr2

spar(bty='l', ps=9)

lp <- predict(f) # Compute linear predictor from full model

# Insert sigma=1 as otherwise sigma=0 will cause problems

a <- ols(lp ~ sz + sg + log(ap) + sbp + dbp + age + wt +

hg + ekg + pf + bm + hx + rx + dtime, sigma=1,

data=psub)

# Specify silly stopping criterion to remove all variables

s <- fastbw(a, aics=10000)

betas <- s$Coefficients # matrix, rows=iterations

X <- cbind(1, f$x) # design matrix

# Compute the series of approximations to lp

ap <- X %*% t(betas)

# For each approx. compute approximation R^2 and ratio of

# likelihood ratio chi-square for approximate model to that

# of original model

m <- ncol(ap) - 1 # all but intercept-only model

r2 <- frac <- numeric(m)

fullchisq <- f$stats['Model L.R.']

for(i in 1:m) {

lpa <- ap[,i]

r2[i] <- cor(lpa, lp)^2

fapprox <- lrm(cvd ~ lpa, data=psub)

frac[i] <- fapprox$stats['Model L.R.'] / fullchisq

}

plot(r2, frac, type='b',

xlab=expression(paste('Approximation ', R^2)),

ylab=expression(paste('Fraction of ',

chi^2, ' Preserved')))

abline(h=.95, col=gray(.83)); abline(v=.95, col=gray(.83))

abline(a=0, b=1, col=gray(.83))

```

After 6 deletions, slightly more than 0.05 of both the LR $\chi^2$ and

the approximation $R^2$ are

lost. Therefore we take as our

approximate model the one that removed 6 predictors. The equation for

this model is below, and its nomogram is in the figure below.

```{r}

fapprox <- ols(lp ~ sz + sg + log(ap) + age + ekg + pf + hx +

rx, data=psub)

fapprox$stats['R2'] # as a check

latex(fapprox)

```

```{r h=6,w=6,cap='Nomogram for predicting the probability of `cvd` based on the approximate model',scap='Approximate nomogram for predicting cause of death'}

#| label: fig-lrcase1-nomapprox

spar(ps=8)

nom <- nomogram(fapprox, ap=c(.1, .5, 1, 5, 10, 20, 30, 40),

fun=plogis, funlabel="Probability",

lp.at=(-5):4,

fun.lp.at=qlogis(c(.01,.05,.25,.5,.75,.95,.99)))

plot(nom, xfrac=.45)

```

```{r echo=FALSE}

saveCap('11')

```